BALANCEING OF REAL ESTATE IN THE BUDGET

Apstrakt

This paper explores how real estate is accounted for in the public sector, focusing on the application of IPSAS 16 and IPSAS 17, which govern the recognition, valuation, and reporting of publicly owned property. By examining examples of initial recognition, later valuation, and removal from records of both investment property and fixed assets, the paper demonstrates how proper use of international accounting standards enhances transparency and efficiency in managing public assets. It also emphasizes the importance of maintaining detailed records on the condition, value, and changes in real estate, which supports accurate financial reporting and strengthens accountability in public resource management.

Članak

Introduction

IAS 16 is one of the four key standards related to real estate. If a property is acquired for resale or is intended for immediate sale, then IAS 12 applies. When property is used as a fixed asset in the regular operations of a public revenue recipient, IAS 17 is relevant. However, if the property (land or buildings) is acquired or constructed to generate rental income or benefit from value increases, IAS 16 is applied.

A single property, such as a building, can fall under both IAS 16 and IAS 17 if part of it is used operationally and part is leased out.

Property, plant, and equipment (fixed assets) are significant items on the balance sheet and greatly influence the financial position and performance of public sector entities.

This paper outlines the purpose and scope of IAS 16, explains the recognition and initial measurement of investment property and fixed assets, details the cost components, procedures for derecognition, and provides examples of accounting entries and recordkeeping for publicly owned real estate.

Objective and scope of the standard

The purpose of IPSAS 16 is to define how investment property should be accounted for, while IPSAS 17 focuses on the accounting treatment of property, plant, and equipment. IPSAS 17 addresses key aspects such as recognizing these items as assets, determining their undepreciated value, and calculating their carrying amount and depreciation.

IPSAS 16 is applied by public revenue entities that use the accrual basis of accounting when recording investment property. Similarly, IPSAS 17 is applied by those same entities for accounting of property, plant, and equipment.

IPSAS 16 covers the recognition, measurement, and disclosure of investment property, while IPSAS 17 applies to all public revenue users, excluding public enterprises.

These standards do not apply to (Vukša & Milojević, 2024):

Biological assets associated with agricultural activity,

Mineral rights and mineral reserves such as oil, natural gas, and similar non- renewable resources.

Other international public sector accounting standards may have different requirements for recognizing property, plant, and equipment. For instance, IPSAS 13 – Leases, requires entities to determine recognition based on whether the risks and rewards of ownership are transferred through the lease agreement (Zupur & Janjetović, 2023). A public revenue entity applies this Standard to property under construction or development, up until the point it qualifies as investment property under IAS 16 – Investment Property.

IAS 17 does not require public revenue users to recognize heritage assets even if they meet the definition and recognition criteria for property, plant, and equipment. However, if a public revenue user chooses to recognize heritage assets, they must follow the disclosure requirements of the Standard and may apply its measurement methods. Heritage assets are defined because of their cultural, environmental, or historical importance and have specific characteristics such as (Paspalj et al., 2024):

Their cultural, environmental, educational and historical value is unlikely to fully reflect their financial value based on market price alone,

Legal or other obligations may impose prohibitions or certain restrictions on disposal by sale,

These assets are often irreplaceable and their value may increase over time, even if their physical condition deteriorates,

Their useful life is difficult to estimate.

Public revenue beneficiaries may hold a large number of heritage assets acquired over many years through various means such as purchase, donations, bequests, and confiscations (Golubović & Janković, 2023). These assets are intended to generate cash inflows, but there may be legal or social restrictions that limit their use for such purposes.

Recognition

Investment assets may be recognized as assets (Radovanović et al., 2024):

When it is probable that future economic benefits or service potential will flow to the beneficiary of the public revenue,

When the cost of the investment property can be measured reliably.

The public revenue beneficiary does not include the costs of routine maintenance of heritage assets in the carrying amount of the investment property. Instead, these costs are recognized as income or expenses when they occur. Routine maintenance costs typically involve labor and minor parts.

The cost of property, plant and equipment should be recognized as an asset (Dašić et al., 2023):

When it is probable that future economic benefits and service potential will flow to the beneficiary of the public revenue, whether in the form of income or a reduction in expenses, If the cost or cost of the asset can be measured reliably.

There must be sufficient certainty that the public revenue user will benefit economically from using the asset, which also means taking on the risks related to it (Bučalina, 2024). For example, right after purchasing or acquiring the asset, the user may learn that the product made with that asset is banned by the authorities or that competitors have a technologically superior asset, reducing the sales potential of the product (Inđić et al., 2023; Neševski & Bojičić, 2024). In the first case, the asset would not meet recognition criteria and the cost should be recorded as an expense for that period. In the second case, the cost of the fixed asset is included in the acquisition or production costs of the product or in the exchange value of the asset (Zekić & Brajković, 2022).

The public expenditure user assesses all costs of property, plant, and equipment at the time they occur. These include initial acquisition or construction costs, as well as subsequent costs related to upgrading, replacing parts, or maintaining the asset.

Initial measurement of investment property

Investment property is initially measured at cost, which includes all acquisition- related expenses. The value of acquired investment property covers the purchase price and all directly attributable costs, such as legal and attorney fees, property transfer taxes, and other transaction expenses (Petrović & Milaš, 2023).

If the company constructs the investment property itself, IAS 17 is applied until the construction or capital improvements are completed and until the asset is transferred to investment property status.

The cost of investment property does not include (Saull et al., 2020):

- Initial operating expenses for activating the investment property,

- Expenses incurred until the normal level of use of the facility is reached,

- Excess costs incurred during the construction of the investment property.

When investment property is purchased on credit, its cost is recorded at the cash payment price, while interest incurred during the loan repayment is recognized as an expense for that period, meaning interest is not capitalized.

Investment property can also be acquired through non-exchange transactions, such as when the government transfers surplus office space to a local public revenue user without compensation, who then leases it at market rates. Investment property may also be acquired through confiscation.

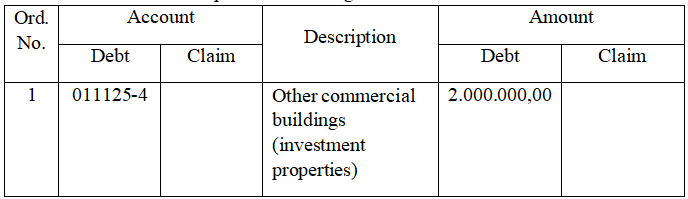

Example: An investment of 2,000,000 dinars was made in a building, recorded as investment property. An invoice from the contractor for 2,000,000 dinars was received, with VAT of 360,000 dinars calculated. At year-end, the fair value of the investment property was determined to be 1,800,000 dinars. Depreciation of 200,000 dinars reflects the proportionate expense over the lease term.

Table 1. Example of accounting in accordance with IPSAS 16

Initial measurement of property, plant and equipment

A single item of property, plant, and equipment that meets the criteria for recognition as an asset should initially be measured at cost. If the asset is acquired in a non-exchange transaction, its cost is determined based on its fair value at the acquisition date (Zhang, 2023). For example, this can occur in cases such as foreclosure. The cost of the asset is its fair value at the acquisition date.

Infrastructure assets

These assets include property, plant and equipment and their accounting is carried out in accordance with IAS 17. These assets have some of their own characteristics (Ang et al., 2023):

- They form part of a system or network,

- They are of a special nature and do not have the possibility of alternative use,

- They are immovable,

- There are restrictions on disposal.

These assets include: road networks, sewage systems, water and electricity supply systems and communication networks.

Elements of cost

The cost of property, plant and equipment includes (Ranta et al., 2024):

1. Invoice price, including import duties and non-refundable sales taxes after deducting trade discounts and rebates,

2. Other costs related to bringing the asset to its intended use, including:

- Costs of employee compensation directly related to the acquisition or construction of property, plant and equipment,

- Costs of preparing the work space,

- Initial delivery costs and handling costs,

- Installation costs,

- Costs of design and engineering supervision,

- Costs of testing whether the asset is functioning normally, less revenue from the sale of products produced during that testing.

3. The estimated cost of dismantling and removing the asset and restoring the site, as well as liabilities arising from the use of the asset for purposes other than the production of inventories during the period.

The cost of property, plant and equipment does not include (Savić et al., 2024):

1. Costs of opening a new facility,

2. Costs of introducing a new product or service,

3. Costs of operating a business at a new location,

4. Administrative and other expenses.

Operating overhead costs are not included in the cost of an asset unless they can be directly and reliably attributed to acquiring a specific asset. Initial and similar costs incurred before the asset is ready for use are excluded from the cost unless necessary to bring the asset to working condition. Losses incurred from maintaining the asset until it reaches its planned performance are not part of the cost but are recognized as expenses in the period incurred.

Measurement after initial recognition of an asset

Measurement is the process of determining the value at which an asset is carried after its initial recognition and inclusion in the financial statements. Two models can be applied for measurement (McAllister & Nase, 2023):

- The cost model implies that property, plant and equipment, after recognition as an asset, are carried at their cost or cost price, less any accumulated depreciation and impairment losses.

- The revaluation model implies that property, plant and equipment are carried at a revalued model that reflects the fair value at the date of revaluation, less any accrued depreciation and impairment losses.

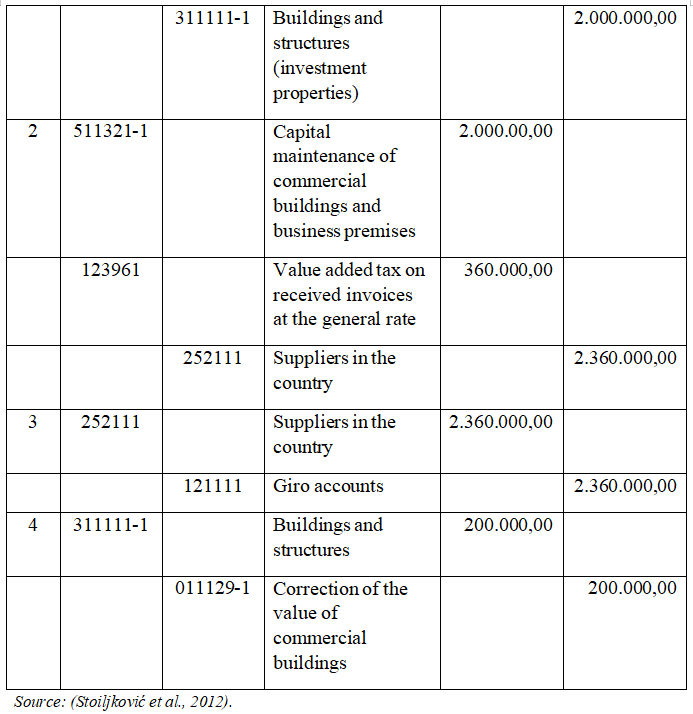

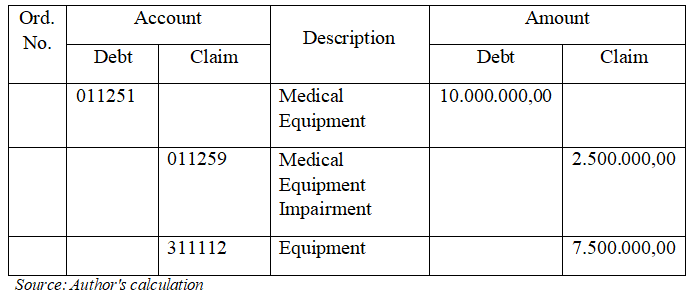

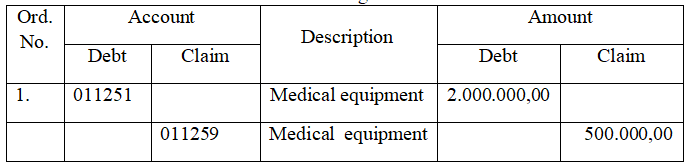

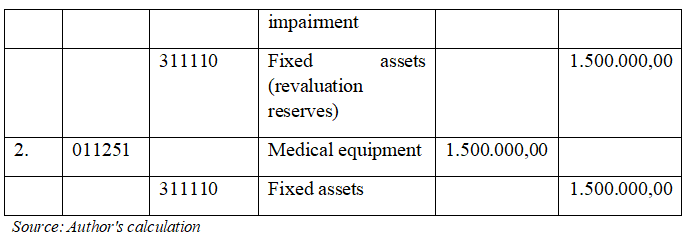

Example: The gross book value of an electromagnetic resonance asset before revaluation is 10,000 dinars, the value adjustment is 2,500,000 dinars, and the net (carrying) value is 7,500,000 dinars. The revaluation rate is 20%. This increases the gross book value by 2,000,000 dinars, the value adjustment by 500,000 dinars, and the net value by 1,500,000 dinars. The revaluation effect is 1,500,000 dinars (2,000,000 - 500,000).

Table 2. Presentation of the balance in the business books before the revaluation

Table 3. Presentation of accounting in accordance with IPSAS 17

Derecognition

When investment property is sold or retired from use and no future economic benefits or service potential are expected, it should be removed from the balance sheet. Investment property can be disposed of by sale or financial lease if there is an option to transfer ownership to the lessee at the end of the lease term (Hemed, 2022). Gains or losses from retirement or disposal are calculated as the difference between net disposal proceeds and the asset’s carrying amount and recognized as income or expense (Li et al., 2019).

Items of property, plant, and equipment should be derecognized when disposed of or when no future benefits are expected. If sold, derecognition occurs on the sale date (Savić et al., 2018), which is when the criteria for sale are met.

Income or expenses from derecognition are recognized at the time of derecognition.

Immovable property owned by the public is acquired or disposed of based on market value assessed by tax or competent authorities through public bidding or written offers (Public Property Act).

Keeping records on the condition, value and movement of real estate in public ownership

Authorities and organizations of the Republic of Serbia, autonomous provinces, local self-government units, public enterprises, capital companies, dependent capital companies, institutions, public agencies, and other legal entities founded by the Republic of Serbia, autonomous provinces, and local self-government units as users or holders of the right to use, must keep special records of real estate in public ownership that they use (Regulation on the Records of Real Estate in Public Ownership).

Special records of real estate users, i.e., holders of the right to use, shall be kept for (Katona & Panfilov, 2018):

1. land in public ownership (construction, agricultural, forest and other land);

2. official building, business premises and parts of the building;

3. residential building, apartment, garage and garage space;

4. real estate for representative purposes;

5. real estate for the purposes of diplomatic and consular missions;

6. other construction objects.

Special records on the value, condition and movement of real estate within the meaning of this regulation include (Katona & Panfilov, 2018):

1. purchase value of real estate;

2. adjustment of the value of real estate;

3. current book value according to the last annual inventory at the time of compiling the balance sheet of users, i.e. holders of the right of use, i.e. according to the last inventory (in cases of status change, change of legal form, opening or conclusion of regular liquidation and bankruptcy proceedings, as well as in other cases provided for by law);

4. movement, i.e. changes in the condition and value of real estate, which are the result of the disposal of real estate (granting for use, leasing, transfer of public property rights to another public property holder, including exchange, alienation, mortgage, investment in capital), acquisition, extension, change of purpose, etc.

Special records of real estate in public ownership are kept individually for each real estate on Form NEP-JS - Data on real estate in public ownership and the user, i.e. the holder of the right of use.

Conclusion

Valuation and recording of real estate in the public sector are crucial parts of financial reporting as they directly impact the true picture of assets, liabilities, and business results of public fund users. The analysis of IPSAS 16 and IPSAS 17 shows that proper application of international accounting standards enables not only accurate recording of real estate values but also better decision-making in managing public assets. Accounting examples demonstrate the need for consistent application of all stages in the lifecycle of real estate—from initial recognition, through subsequent valuation, to derecognition.

Special emphasis is placed on the obligation to maintain special records of real estate in public ownership, which forms the basis for efficient management, investment planning, risk assessment, and transparency towards citizens and oversight bodies. Introducing fair value as the dominant measurement model contributes to a more objective presentation of the real economic value of public assets, thereby strengthening confidence in public sector financial statements.

In modern conditions, ensuring an integrated and standardized accounting approach, along with ongoing training and professional support for public fund users, is essential for improving public management quality and rationalizing budget spending. This lays the foundation for enhancing fiscal responsibility and the long-term sustainability of public finances.

Reference

2.Bučalina M.A. (2024). Prikaz knjige: Faktori odlučivanja i kreiranje lojalnosti potrošača - Tankosić Mirjana, Bulut-Bogdanović Ivana: Ponošanje potrošača u savremenom poslovnom okruženju, Fakultet društvenih nauka, Beograd, 2024. Društveni horizonti, 3 (6), 103-106.

3.Dašić, B., Župljanić, M. & Pušonja, B. (2023). Uloga regulatornog okvira na

prilive stranih direktnih investicija. Akcionarstvo, 29(1), 95-112.

4.Golubović, M., Janković, G. (2023). Priliv stranih direktnih investicija u funkciji pobolјšanja konkurentnosti privrede Republike Srbije. Održivi razvoj, 16 (1), 19-31. https://doi.org/10.5937/OdrRaz2301019G

5.Hemed, R. I. (2022). Normative arrangement of financial innovations in banking. Finansijski savetnik, 27(1), 25–64.

6.Inđić, M., Pjanić, M. & Đaković, M. (2023). Uticaj makroekonomskih faktora na tržšnu kapitalizaciju u bivšim Jugoslovenskim republikama sa moderacijom bivših republika koje ne koriste euro. Akcionarstvo, 29 (1), 151-168.

7.Katona, A., & Panfilov, P. (2018). Building Predictive Maintenance Framework for Smart Environment Application Systems. Vol. 1. DAAAM International Vienna, 2018. Web. https://doi.org/10.2507/29th.daaam.proceedings.xxx

8.Li, Y., Kubicki, S., Guerriero, A., & Rezgui, Y. (2019). Review of building energy performance certification schemes towards future improvement. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 113, 109244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2019.109244

9.McAllister, P., & Nase, I. (2023). Minimum energy efficiency standards in the commercial real estate sector: A critical review of policy regimes. Journal of Cleaner Production, 393, 136342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136342

10.Mertzanis C, Marashdeh H, Houcine A (2023) Do financing constraints affect the financial integrity of firms? Int Rev Econ Financ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2023.12.004

11.Neševski, A. & Bojičić, R. (2024). Analiza uloge sopstvenih prihoda u

finansiranju rashoda. Akcionarstvo, 30(1), 95-112.

12.Paspalj, M., Paspalj, D. & Milojević, I. (2024). Održivost savremenih ekonomskih sistema. Održivi razvoj, 6 (1), 33-45.

https://doi.org/10.5937/OdrRaz2401033P

13.Petrović, S. & Milaš, M. (2023). Mediji kao model delovanja i komuniciranja u političkom sistemu Republike Srbije. Društveni horizonti, 3 (6), 85-99. https://doi.org/10.5937/drushor2306085P

14.Public Property Act - Zakon o javnoj svojini („Sl. glasnik RS“ broj. 108/2016

i 113/2017).

15.Radovanović, Ž., Mihailović, N. & Rajnović, Lj. (2024). Impact of the implementation of the fatf recommendations on the financial performance of the gambling sector. Akcionarstvo, 30(1), 77-94.

16.Ranta, T., Karhunen, A., & Laihanen, M. (2024). The effect of fuels and other variables on the price of district heating in Finland. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 209, 115086.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2024.115086

17.Regulation on the Records of Real Estate in Public Ownership - Uredba o evidenciji nepokretnosti u javnoj svojini („Službeni glasnik RS“ br. 70/2014, 19/2015 i 83/2015).

18.Saull A et al (2020) Can digital technologies speed up real estate transactions? J Prop Invest Financ 38(4):349–361. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPIF-09-2019-0131

19.Savić, A, Mihajlović, M.,. & Ristić, D. (2024). Menadžerski aspekti egzistiranja preduzeća na savremenom tržištu, Ekonomski izazovi, 13 (26), 15-24. https://doi.org/10.5937/EkoIzazov2426015S

20.Gojkov, D. (2024) Karakteristike objekata prava i državine, Revija prava javnog sektora, 4(1): str. 23-34. http://www.revijaprava.in.rs/

21.Stoilјković, S., Stojilјković, D., Guzina, V., Milojević, I. & Albaneze, Ž. (2012). Priručnik za primenu međunarodnih računovodstvenih standarda za javni sektor, Beograd.

22.Slavković, G., Milanović A., Obrić B. (2024). Support of topsis and dematel methods in the preparing and using financial reports of textil industry in the business decisions process, ITB, 2 (1), 07-24.

23.Vukša, S. & Milojević, I. (2024). Održivost računovodstva kao informacionog sistema. Održivi razvoj, 6 (2), 23-33. https://doi.org/10.5937/OdrRaz2402023V

24.Zekić, M. & Brajković, B. (2022). Uloga finansijskog menadžmenta u preduzeću, Finansijski savetnik, 27(1), 7-24.

25.Zhang Q (2023) Digital transformation of real estate industry: opportunities, challenges and strategic suggestions. Adv Econ, Manag Political Sci 3(1):277–281. https://doi.org/10.54254/2754- 1169/3/2022794

Zupur, M. & Janjetović, M. (2023). Sustainability of personal selling marketing in the modern market. Održivi razvoj, 16 (2), 7-20. https://doi.org/10.5937/OdrRaz2302007Z

Objavljeno u

God. 11 Br. 2 (2025)

Ključne reči

🛡️ Licenca i prava korišćenja

Ovaj rad je objavljen pod Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

Autori zadržavaju autorska prava nad svojim radom.

Dozvoljena je upotreba, distribucija i adaptacija rada, uključujući i u komercijalne svrhe, uz obavezno navođenje originalnog autora i izvora.

Zainteresovani za slična istraživanja?

Pregledaj sve članke i časopise