RAZJAŠNJAVANJE KONEKCIJE PERCIPIRANA PREKVALIFIKOVANOST‒NAMERA ODLASKA IZ ORGANIZACIJE: POSREDNIČKA ULOGA ZADOVOLJSTVA POSLOM

Apstrakt

U organizacionom sistemu koji se konstantno razvija, vršenje strateškog manevrisanja zaposlenih je neophodnost. Širok spektar percepcija zaposlenih zahteva menadžersku veštinu koja treba da suzbije često konsekventne, ali nepoželjne stavove i ponašanja zaposlenih. Primarni cilj naučnoistraživačkog rada bio je da podrobnije istraži složenost sve prisutnije problematike ove vrste, odnosno da ispita konekciju „percipirana prekvalifikovanost‒namera odlaska iz organizacije”, te dodatno, prouči da li zadovoljstvo poslom posreduje u gore pomenutoj relaciji. Uzorak istraživanja obuhvatio je 151 ispitanika, srpskih državljana, koji su prema zvaničnim podacima činili deo nacionalne radne snage na kraju 2022. godine (vreme popunjavanja upitnika). Podaci prikupljeni putem adekvatno strukturisanog Google Forms online upitnika podvrgnuti su naknadnoj analizi korišćenjem statističkih alata IBM SPSS Statistics 26 i SmartPLS 4. Sprovedeno istraživanje empirijski je testiralo i potvrdilo pretpostavku da percepcija zaposlenog o prekvalifikovanosti (prekoračenje zahteva trenutnog radnog mesta) stvara plodno tlo za razvoj njegovog/njenog nezadovoljstva (niski nivoi zadovoljstva poslom), koje može kulminirati namerom napuštanja posla. Rad doprinosi aktuelnoj debati o konsekventnosti relacije „percepcije‒ stavovi‒ponašanje” zaposlenih i može poslužiti kao dragocena referentna tačka u konstruisanju dugoročnih planova i strategija organizacije.

Članak

Introduction

Human resources are the most prized organizational asset. For that reason, workforce preservation represents every successful organization’s top priority. Yet, against the employees’ preservation stands their potential withdrawal intention. Employees’ intention to leave the organization represents the behavioral manifest which may be caused by a variety of reasons ‒ some internal (which employees may control either totally or partially), and some external (over which employees can have very little or no influence at all). Organizational literature acknowledges perceived overqualification as one of these internal factors, and declares it to be the cause of the aforementioned employees’ unwanted behavior in the context of workforce stability.

Given the insufficient empirical evidence and many unanswered questions related to this issue, the research direction and aim of the paper were established. The intent was to investigate the relationship between employees’ perceived overqualification and intention to leave the organization, as well as the eventual mediating effect of job satisfaction within it. All this is done through a concrete analysis of the effects of perceived overqualification on the attitude/behavioral intentions of national workers employed in the territory of the Republic of Serbia. The exploratory model depicted perceived overqualification as an independent variable, whilst job satisfaction and intention to leave the organization were framed as dependent variables.

The research is divided into four sections. The first section deals with the theoretical underpinnings of the study, whilst the authors underline the significance of the research variables ‒ perceived overqualification, job satisfaction, and intention to leave the organization ‒ simultaneously describing them. The formulation of hypotheses and a summary of prior research in the field follow. In the second section, the research technique and methodology explanation are provided. The questionnaire employed, the methods used for the data analysis, and the research sample are all presented and described. The third section relates to the empirical portion of the study, in which the authors discuss data previously processed using IBM SPSS Statistics 26 and SmartPLS 4 statistical software packages, as well as employed PLS-SEM analysis, aiming to validate the hypothesized correlations. The entire study ends with conclusions ‒ theoretical and empirical ramifications, research limitations, and suggested directions for future examination.

Theoretical background

Theoretical approaches to the observed phenomena reveal scholars’ unity regarding its defining. Videlicet, numerous authors (Johnson, Johnson, 2000; Biaobin et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2021; Maltarich et al., 2011; Jolović, Bobera, 2019; Maynard, Parfyonova, 2013) are united in the assertion that perceived overqualification represents an individual’s belief that the skill set he/she possesses exceeds the requirements of the job he/she performs, i.e., that his/her education, experience, as well as knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAOs) are more extensive than those needed for his/her current work position. According to Erdogan and Bauer’s (2021) terminology, overqualification cultivates a sense of being deprived of the job one deserves, and is subsequently associated with a variety of detrimental effects on both employees and organizations. In other words, overqualification can often be seen as an antecedent of employees’ negative job attitudes, as well as a driver of behaviors that are unfavorable from the organization’s point of view (Erdogan, Bauer, 2009; Liu et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2024).

Work-related attitude relevant for this research ‒ job satisfaction, can be defined as a positive or pleasurable emotional state that arises from the appraisal of one’s job (Alfes et al., 2016; Parveen et al., 2017), whilst observed unfavorable employees’ behavior ‒ intention to leave the organization, can be conceptualized as the combination of one’s desire to leave current and search for alternative employment, along with the aspiration to pursue more favorable career development opportunities and fully actualize personal professional potential (Chen et al., 2021; Jolović, Berber, 2021).

The studies examining the overqualification‒turnover nexus (Andrade et al., 2023; Yildiz et al., 2017; Rasheed et al., 2024; Vinayak et al., 2021; Ballesteros-Leiva et al., 2023; Ye et al., 2017; Rasheed et al., 2022; Li et al., 2020; Biaobin et al., 2021; Harari et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2021; Piotrowska, 2022; Liu, Wang, 2012; Mah, Huang, and Yun, 2024; Mah, Shin, and Min, 2024) demonstrate that perceived overqualification is a statistically significant, positive predictor of employees’ intention to leave the organization. More specifically, perceived overqualification can produce dissatisfaction, trigger job search, and ultimately result in turnover behavior (Maynard, Parfyonova, 2013). Therefore, perceived overqualification is negatively related to job satisfaction (Alfes et al., 2016; Johnson, Johnson, 2000; García- Mainar, Montuenga-Gómez, 2020; Erdogan, Bauer, 2009; Erdogan et al., 2011; Wassermann et al., 2017; Andrade et al., 2023; Arvan et al., 2019; Harari et al., 2017; Pan, Hou, 2024; Lobene et al., 2014). The scientific literature (Tian‐Foreman, 2009; Azeez et al., 2016; Alam, Asim, 2019; Andrade et al., 2023; Scanlan, Still, 2019; Mobley, 1977; Ramalho Luz et al., 2018; George, Sreedharan, 2023; Lee et al., 2017) offers strong support for the stance that there is a negative relationship between employees’ job satisfaction and intention to leave the organization. Finally, the mediating effect of job satisfaction in the perceived overqualification‒intention to leave the organization relationship has been acknowledged and only briefly examined by several authors (Maynard, Parfyonova, 2013; Kengatharan, 2020).

Organizational literature’s acknowledged findings justify the construction of four distinct research hypotheses:

· H01: A statistically significant, negative relationship exists between perceived overqualification and job satisfaction;

· H02: A statistically significant, negative relationship exists between job satisfaction and intention to leave the organization;

· H03: A statistically significant, positive relationship exists between perceived overqualification and intention to leave the organization;

· H04: A statistically significant, mediating role of job satisfaction exists in the relationship between perceived overqualification and intention to leave the organization.

Research methodology

Data collection methodology

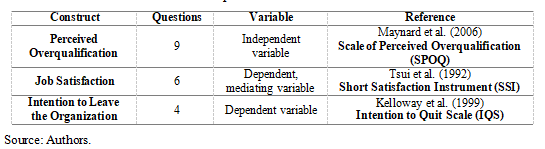

To gather original empirical data, the Google Forms online questionnaire was utilized and distributed in November 2022. A total of 28 questions were posed ‒ 9 concerning respondents’ demographic characteristics (gender, age, region of residence, etc.) and current employment details, and 19 addressing the main research issue (these questions were extracted from relevant and verified survey questionnaires which are referenced in Table 1).

Table 1. Formulation of the research questionnaire

The respondents at their disposal had the five-point Likert scale of psychometrics to mark the answers that most closely correspond to their perceptions and current attitudes toward their work environment. A rating of 1 indicated total disapproval of the assertions, while a rating of 5 was indicative of absolute assent to the declared assertions.

Sampling methodology

A cohort of 151 individuals, the Republic of Serbia’s residents, who were proved to be in employment at the time of completing the questionnaire (and apropos verified as eligible for the survey) comprised the research sample. The obtained respondents’ age demographics structure was uneven ‒ Millennials (born between 1980-2000) made up by far the majority of contributors (even 120 of them responded to the survey questions), while Baby Boom generation members (born between 1946-1964) made up the smallest fraction of the sample (only 6 of them took part in the research). The distinct IT literacy level of the age generations involved in the research partially justifies this state of affairs (not to mention the fact that the Baby Boomers are nearing the end of their professional lifetime).

When it comes to the frequency, it can be noted that within the research cohort, female employees outnumbered male employees, with 88 respondents (58.3%), compared to 63 respondents (41.7%). Obtained region-specific data reveal that employees from all regions of the Republic of Serbia participated in the survey relatively evenly (Belgrade region encompassed 28 respondents, South and Eastern Serbia region 54, Šumadija and Western Serbia region 55, Vojvodina region 12, while Kosovo and Metohija region encompassed 2 respondents).

The average respondent is positioned high on the academic ladder (the survey included 54 respondents with a Master of Academic Studies degree and a Bachelor of Academic Studies degree ‒ 35.8% of the research cohort each). Higher School, Vocational High School/Gymnasium, and Doctoral Academic Studies were completed by 5, 30, and 8 respondents, respectively.

As previously stated, only employed individuals took part in the study. Among them, there were as many as 19 respondents (12.6% of the research cohort) who reported performing duties without a formal contract in their present organization (“illegal” workers). In the observed sample, 68 respondents were hired for an indefinite period, and 51 were hired for a predetermined period under fixed-term contracts (45.0% and 33.8%, respectively). Engagements outside the formal employment framework (additional/short- term/intermittent/occasional work) were documented in the case of 13 respondents (8.6% of the research cohort). Full-time employment arrangements (40 hours per week) predominated among the workers surveyed, accounting for 109 respondents (72.2% of the research cohort). In contrast, 42 respondents, representing 27.8% of the research cohort, were engaged in part- time employment.

When it comes to the review of the surveyed workers’ professions, nearly half (75 of them, 49.7% of the research cohort) held the position of Professional worker-specialist for a specific field in the current organization. The number of Technical and operational workers was the smallest ‒ only 6 respondents (4% of the research cohort). According to the position in the organization, the remaining respondents in the sample can be classified into the following categories: Physical worker ‒ 12 respondents, Service worker, merchant or craftsman ‒ 18, Administrative worker ‒ 15; Manager ‒ 15; and Owner/Partner ‒ 10 respondents.

Regarding the length of service, it is important to emphasize that the average respondent’s relatively young age justifies the obtained research findings ‒ the number of employees with tenure ranging from 16 to 20, as well as 20 years and more within the organization was comparatively low, comprising respectively 3 and 10 respondents; whilst the number of employees who were engaged within the organization “shorter than 1 year” was significantly higher (34 respondents). Furthermore, the results obtained revealed that 68 respondents had a tenure of 1-5 years with their employer, 26 had been employed for 6-10 years, and 10 for 11-15 years.

As per the observed sample’s monthly salaries data, the fact worth highlighting indicates that 151 respondents’ monthly income ranged from up to 30,000 dinars (26 respondents), 30,001-60,000 dinars (66), 60,001-90,000 dinars (32), 90,001-120,000 dinars (15), and over 120,000 dinars (12 respondents).

Data processing methodology

In order to investigate the nature of relations between perceived overqualification and intention to leave the organization, the research process included several research methods and data analysis tactics ‒ the content and thematic analysis methods were utilized for the purpose of the nexus’ empirical identification, whilst the analysis and synthesis methods were employed as reasoning methods. Prior to performing pivotal data evaluation through the mediation model approach within SmartPLS 4 statistical software, another statistical tool

– IBM SPSS Statistics 26, was employed for the purpose of determining the average respondent’s profile (calculation of frequencies) (Ringle et al., 2022; IBM Corporation, 2019). The testing of the proposed research model is done using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) via SmartPLS.

Research results and discussion

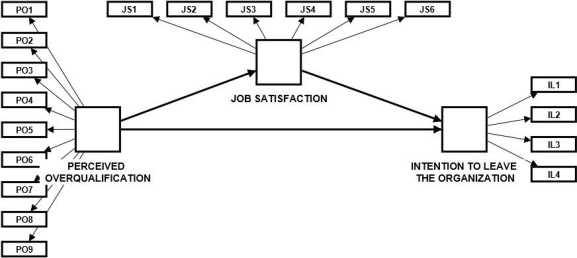

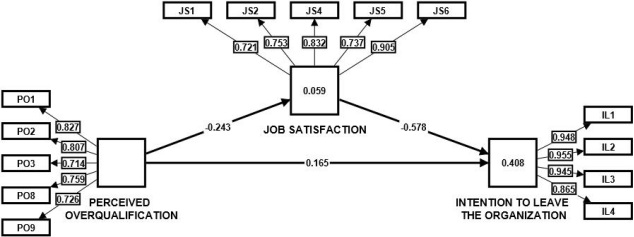

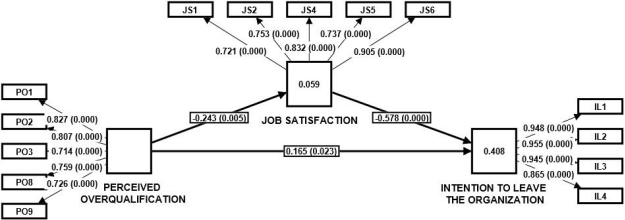

PLS-SEM is emerging as a preferred approach for estimating structural equation models (Hair et al., 2014; Wong, 2013). Figure 1 shows the reflective measurement model that was developed for this study ‒ its 19 indicators, three constructs, and their accompanying structural linkages. The measurement model’s detailed overview follows.

Figure 1. Measurement model overview

Source: Authors, SmartPLS 4 software employed.

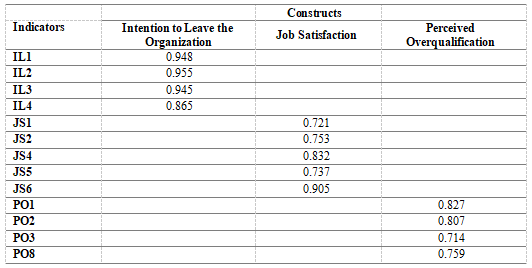

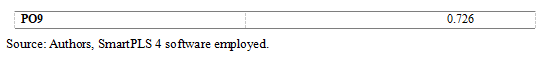

Outer Loadings for reflecting indicators are shown at the beginning of the overview with the aim of estimating their reliability. The criterion is established at a minimum of 0.708 for each indicator’s value, implying that if the indicator reaches a prescribed value, a particular research construct explains over 50% of the variance within that indicator (Hair et al., 2019; Jolović, Jolović, 2022; Jolović, Jolović, 2023).

The reliability testing of research indicators gave the following results. The indicators JS3 (0.548), PO4 (0.454), PO5 (0.641), PO6 (0.582), and PO7 (0.642), which according to the

computation did not meet the set reliability standard, were excluded from the subsequent calculation. Table 2 contains a list of the ones that did meet set standards, whilst Figure 2 graphically presents the remaining indicators.

Table 2. Verification of indicators’ reliability

Figure 2. Verification of indicators’ reliability

Source: Authors, SmartPLS 4 software employed.

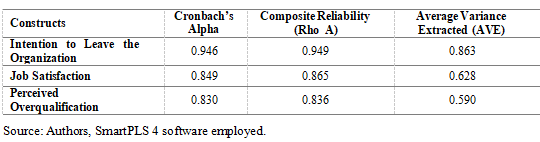

Utilizing Cronbach’s Alpha and Composite Reliability (Rho_A criteria), the internal consistency reliability of each construct measure is subsequently evaluated. The threshold for each construct reliability value to be identified as suitable for the study is established at 0.70 or higher (up to a value of 0.95, as surpassing this threshold may give rise to discussions concerning the potential redundancy of the indicators) (Hair et al., 2019; Jolović, Jolović, 2022; Jolović, Jolović, 2023).

Additionally, using the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) metric, the convergent validity of each construct measure is assessed. The criterion is established at a minimum of 0.50, implying that if the prescribed value is obtained, constructs are capable of explaining no less than 50% of the variance within their associated items (Hair et al., 2019; Jolović, Jolović, 2022; Jolović, Jolović, 2023).

Results of research constructs’ internal consistency reliability and convergent validity testing are displayed in Table 3. All constructs will be included in the further calculation since they all satisfy the prescribed standards (of 0.70 and 0.50, respectively).

Table 3. Verification of constructs’ internal consistency reliability and convergent validity

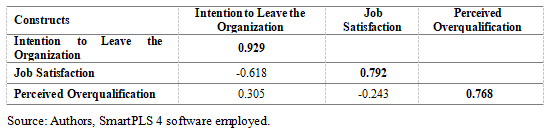

The Fornell-Larcker Criterion is employed to gauge the discriminant validity of each construct measure. Hair and co-authors (2019) argue that this criterion should demonstrate the degree to which a singular construct conceptually stands apart from all other constructs integrated into the research model (the AVE value of each construct is contrasted with the squared inter-construct correlation of that and all other reflectively measured constructs; if the shared variance for all constructs does not exceed their individual AVE values, discriminant validity is confirmed) (Hair et al., 2019; Jolović, Jolović, 2022; Jolović, Jolović, 2023).

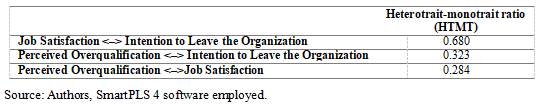

Supplementary examination of the discriminant validity of each construct measure is done by utilizing the Heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT). This ratio is calculated as the mean of the item correlations across constructs (heterotrait-heteromethod correlations) relative to the geometric mean of the average correlations for the items measuring the same construct (monotrait-heteromethod correlations) (Hair et al., 2019). When HTMT levels are high, discriminant validity issues exist. Structured models have a threshold value of 0.90 (Hair et al., 2019).

The results of both discriminant validity tests for research constructs are presented respectively in Table 4 and Table 5. All constructs met the previously described criteria, indicating they all possess discriminant validity and may be treated as distinct entities within this research.

Table 4. Verification of constructs’ discriminant validity (Fornell-Larcker criterion)

Table 5. Verification of constructs’ discriminant validity (Heterotrait-monotrait ratio ‒ HTMT)

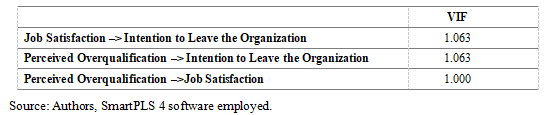

The structural model’s evaluation comes next in the stepwise interpretation of the PLS-SEM data after the measurement model’s estimation has been deemed satisfactory. To ensure it does not influence the regression findings, collinearity in a structural model should be investigated first. Calculating the inner VIF values in this method involves using the latent variable values of the predictor constructs in partial regression. The acceptable value’s limit is at 5 or lower, as greater values may signal potential collinearity issues between the predictor constructs (Hair et al., 2019; Jolović, Jolović, 2022; Jolović, Jolović, 2023).

The structural research model’s collinearity testing findings are displayed in Table 6. The constructs all adhered to the earlier discussed threshold of 5 indicating their independence from one another and confirming that changes in one do not have an impact on changes in the others, as well as the opposite.

Table 6. Verification of the structural research model’s collinearity

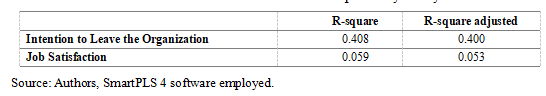

The R2 examination of the endogenous constructs is presented next (Table 7 results). The coefficient of determination (R Square ‒ R2) quantifies the proportion of variance explained in each endogenous construct, serving as a verified measure of the model’s explanatory ability (power). It reveals what amount of change in the dependent variable can be explained by one of more independent variables. R2 values for endogenous latent variables are typically interpreted as follows: 0.26 (substantial), 0.13 (moderate), 0.02 (weak); or even 0.67 (substantial), 0.33 (moderate), 0.19 (weak) (Hair et al., 2019). Nevertheless, the acceptability of the R2 values depends on the specific research context and the discipline of the study.

The R2 result for the construct Intention to Leave the Organization is 0.408, indicating that the research model demonstrates moderate to substantial predictive ability for the mentioned variable. In contrast, the R2 result for construct Job Satisfaction is 0.059, suggesting that the constructed research model exhibits weak predictive ability in explaining this variable.

Table 7. Verification of the structural research model’s explanatory ability

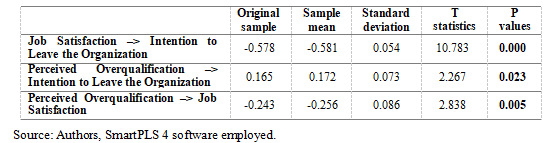

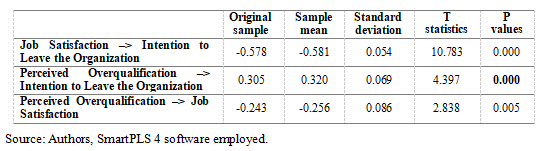

Finally, subsequent to the demonstration of the model’s explanatory ability, the structural path significance check is performed. Table 8 provides information on the outcomes of the Bootstrapping method and the t-test for the 5% and 1% significance level. In total, 5,000 repetitions of the Bootstrapping technique were performed.

The calculation described confirmed the existence of three direct and statistically significant relationships between:

· Perceived Overqualification and Job Satisfaction ‒ negative relation (β=-0.243, t=2.838, p=0.005; p<0.05 and p<0.01), which consequently provides sufficient evidence for the acceptance of the H01 hypothesis;

· Job Satisfaction and Intention to Leave the Organization ‒ negative relation (β=-0.578, t=10.783, p=0.000; p<0.05 and p<0.01), which consequently provides sufficient evidence for the acceptance of the H02 hypothesis;

· Perceived Overqualification and Intention to Leave the Organization ‒ positive relation (β=0.165, t=2.267, p=0.023; p<0.05), which consequently provides sufficient evidence for the acceptance of the H03 hypothesis.

These first two findings enable examination of the possible mediating role of Job Satisfaction variable in the association between the variables Perceived Overqualification and the employee’s Intention to Leave the Organization.

Table 8. Verification of the structural research model’s direct effects

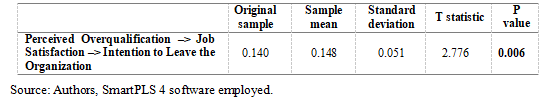

Last but not least, the findings shown in Table 9 undoubtedly reveal whether the variable Job Satisfaction mediates the relationship between the variables Perceived Overqualification and Intention to Leave the Organization. This effect appears to be statistically significant (β=0.140, t=2.776, p=0.006; p<0.05 and p<0.01), which consequently provides sufficient evidence for the acceptance of the H04 hypothesis.

Since there is a confirmed statistically significant indirect (mediating) effect in the relation Perceived Overqualification ‒> Job Satisfaction ‒> Intention to Leave the Organization, and since the direct effect Perceived Overqualification ‒> Intention to Leave the Organization also exists and it is significant, it can be concluded that mediation within this model can be described as partial. For the purpose of distinguishing whether this partial mediation is complementary or competitive, the following calculation will be performed (precisely, multiplying β coefficients of corresponding p values from direct relationships in the research model), according to Hair and co-authors (2021) proposition:

p1 x p2 x p3 = -0.243 x (-0.578) x 0.165 = 0.02

Given that the calculated result is positive, it can be inferred that within the research model, complementary partial mediation is present (for clarification, complementary partial mediation refers to a scenario where both the direct and indirect effect p1 x p2 point in the same direction; and where the product of the direct effect and the indirect effect p1 x p2 x p3 remains positive) (Hair et al., 2021).

Table 9. Verification of the structural research model’s indirect (mediating) effect

The final critical step in evaluating the structural research model involves assessing the total effects registered (Table 10). Total model effects are consistent with previous results, and once again confirm the set research hypotheses (by observing the entire model effects, it is possible to conclude that the effect on the relation Perceived Overqualification ‒> Intention to Leave the Organization is strengthened – p value changed from 0.023 to 0.000).

Table 10. Verification of the structural research model’s total effects

Figure 3 shows the reflective structural model used in the research, and its detailed results. Figure 3. Structural research model’s results

Source: Authors, SmartPLS 4 software employed.

Conclusion

The conducted research confirmed that intention to leave the organization does not have to be “triggered” solely by the employee’s dissatisfaction with the salary, relations in the work collective or lack of advancement opportunities ‒ that is, by the factors that most frequently capture the management’s attention and raise owner’s concerns regarding the sustainability of the work team. The employee’s individual impression of “superiority” regarding the work being performed, and/or the expertise of work collective/co-workers who are simultaneously performing the same work “unlocks” an entirely new threat. More specifically, the employee’s perception of himself/herself as dominant over others (regardless of genuine reality) significantly affects his/her behavior in the context of staying/leaving current job position. As assumed by the H01 research hypothesis and the prior empirical evidence, the employee’s perceived overqualification and, therefore, superiority in the workplace negatively affect his/her job satisfaction (β=-0.243, t=2.838, p=0.005; p<0.05 and p<0.01, results shown in Table 8).

The individual’s realization that he/she has much more potential than the organization initially recognizes in him/her, i.e., which the organization nurtures and ultimately pays for, causes frustration and dissatisfaction with work duties, and often develops into discontentment with the workplace and thoughts of resigning (high job satisfaction, on the other hand, is associated with less frequent development of the desire to quit). This observation is in line with the H02 hypothesis, which states that high job satisfaction is negatively associated with a likelihood of leaving the organization (β=-0.578, t=10.783, p=0.000; p<0.05 and p<0.01, results shown in Table 8). Additionally, the research confirmed the H03 hypothesis, according to which perceived overqualification directly and positively affects the employee’s intention to leave the organization (β=0.165, t=2.267, p=0.023; p<0.05, results shown in Table 8).

The central research hypothesis H04, which reads “A statistically significant, mediating role of job satisfaction exists in the relationship between perceived overqualification and intention to leave the organization”, was confirmed by the following results available in Table 9 (β=0.140, t=2.776, p=0.006; p<0.05 and p<0.01). This mediation is justly evaluated (by Hair and co-authors’ “p1 x p2 x p3” equation) as complementary partial mediation.

From a comparison of these research findings with earlier literature evidence, one can draw the conclusion that novel findings support the earlier empirical conclusions of distinguished scholars (Maynard, Parfyonova, 2013; Rasheed et al., 2022; Rasheed et al., 2024; Kengatharan, 2020; Andrade et al., 2023; Yildiz et al., 2017; Vinayak et al., 2021; Ye at al., 2017; Li et al., 2020; Biaobin et al., 2021; Harari et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2021; Alfes et al., 2016; Johnson, Johnson, 2000; Mah, Shin, and Min, 2024; Erdogan, Bauer, 2009; Erdogan et al., 2011; Arvan et al., 2019; Lobene et al., 2014; Tian‐Foreman, 2009; Azeez et al., 2016; Alam, Asim, 2019; Scanlan, Still, 2019; Mobley, 1977; Ramalho Luz et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2015; Liu, Wang, 2012; Maltarich et al., 2011; Wassermann et al., 2017). The research question that merits further research concerns the opposite scenario ‒ if an employee feels unqualified for the work position he/she presently holds, which behavior will prevail ‒ the one to leave the organization (given his/her sensation that he/she cannot keep up with the pace of the work team and adequately respond to workplace demands) or the one to hold onto a position he/she is not “up to” (despite the fact that he/she lacks the knowledge and abilities necessary for mentioned work position). Examining research variable relationships while accounting for objective overqualification might also be a sound research concept.

This research contributes to the frontiers of management literature and may serve as a great reference point for the timely building of plans, strategies, and actions for (practically) all organizations that employ a diverse workforce and aspire for its sustainability. The study’s limitations include the sample’s modest size (in relation to the total number of employed people in the Republic of Serbia), the study’s exclusive focus on the national labor market which prevents generalization of the research’s conclusions (a broader regional perspective could have been considered), the uneven representation of respondents from different demographic groupings, having distinct living and working conditions (which is a drawback associated with the study’s small sample size), and the utilization of an electronic online questionnaire (an alternative approach, such as conducting interviews, could have been utilized to gain a deeper and more nuanced understanding of employees’ individual perspectives and professional attitudes). Nonetheless, if the advantages and drawbacks of the completed research were compared and weighed, the advantages would still prevail.

Acknowledgments

This research has been supported by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (Contract No. 451-03-65/2024-03/200156) and the Faculty of Technical Sciences, University of Novi Sad through project “Scientific and Artistic Research Work of Researchers in Teaching and Associate Positions at the Faculty of Technical Sciences, University of Novi Sad” (No. 01-3394/1).

This research has also been supported by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (Contract No. 451-03-47/2023- 01/200005) and the Institute of Economic Sciences in Belgrade.

This research has also been supported by the East-European Center for Research in Economics and Business (ECREB), Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, West University of Timișoara.

Reference

2.Alfes K., A. Shantz, and S. Van Baalen. 2016. Reducing Perceptions of Overqualification and Its Impact on Job Satisfaction: The Dual Roles of Interpersonal Relationships at Work. Human Resource Management Journal 26, (1): 84-101.

3.Andrade L., C. Santos, and L. Faria. 2023. The Mediating Effect of Job Satisfaction on the Relationship between Perceived Overqualification, Turnover Intention and Job Performance among Call Center Employees. Polish Psychological Bulletin 54, (4): 262- 271.

4.Arvan M. L., S. Pindek, S. A. Andel, and P. E. Spector. 2019. Too Good for Your Job? Disentangling the Relationships between Objective Overqualification, Perceived Overqualification, and Job Dissatisfaction. Journal of Vocational Behavior 115, (1): 1- 14.

5.Azeez R. O., F. Jayeoba, and A. O. Adeoye. 2016. Job Satisfaction, Turnover Intention and Organizational Commitment. Journal of Management Research 8, (2): 102-114.

6.Ballesteros-Leiva F., S. St-Onge, and S. Arcand. 2023. Overqualification and Turnover Intention. Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations 78, (2): 1-15.

7.Biaobin Y., Q. Lin, L. Yi, L. Qian, H. Dan, and C. Yiwei. 2021. The Effect of Overqualification on Employees’ Turnover Intention: The Role of Organization Identity and Goal Orientation. Journal of Advanced Management Science 9, (1): 17-21.

8.Chen G., Y. Tang, and Y. Su. 2021. The Effect of Perceived Over-qualification on Turnover Intention from a Cognition Perspective. Frontiers in Psychology 12, (1): 1-15.

9.Erdogan B., and T. N. Bauer. 2009. Perceived Overqualification and Its Outcomes: The Moderating Role of Empowerment. Journal of Applied Psychology 94, (2): 557-565.

10.Erdogan B., and T. N. Bauer. 2021. Overqualification at Work: A Review and Synthesis of the Literature. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 8, (1): 259-283.

11.Erdogan B., T. N. Bauer, J. M. Peiró, and D. M. Truxillo. 2011. Overqualified Employees: Making the Best of a Potentially Bad Situation for Individuals and Organizations. Industrial and Organizational Psychology 4, (2): 215-232.

12.García-Mainar I., and V. M. Montuenga-Gómez. 2020. Over-qualification and the Dimensions of Job Satisfaction. Social Indicators Research 147, (2): 591-620.

13.George P., and N. V. Sreedharan. 2023. Work Life Balance and Transformational Leadership as Predictors of Employee Job Satisfaction. Serbian Journal of Management 18, (2): 253-273.

14.Hair J. F. Jr., G. T. M. Hult, C. M. Ringle, M. Sarstedt, N. P. Danks, and S. Ray. 2021. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook. Springer Nature, Cham.

15.Hair J. F. Jr., J. Risher, M. Sarstedt, and C. M. Ringle. 2019. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review 31, (1): 2-24.

16.Hair J. F. Jr., M. Sarstedt, L. Hopkins, and V. G. Kuppelwieser. 2014. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM): An Emerging Tool in Business Research. European Business Review 26, (2): 106-121.

17.Harari M. B., A. Manapragada, and C. Viswesvaran. 2017. Who Thinks They’re a Big Fish in a Small Pond and Why Does It Matter? A Meta-analysis of Perceived Overqualification. Journal of Vocational Behavior 102, (1): 28-47.

18.IBM Corporation. 2019. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows: Version 26.0. IBM Corporation, New York.

19.Johnson G. J., and W. R. Johnson. 2000. Perceived Overqualification and Dimensions of Job Satisfaction: A Longitudinal Analysis. The Journal of Psychology 134, (5): 537- 555.

20.Jolović I., and D. Bobera. 2019. Analiza uloge projektnog menadžera u upravljanju istraživačko-razvojnim projektom. Oditor 5, (3): 38-52.

21.Jolović I., and N. Berber. 2021. Uticaj praksi menadžmenta ljudskih resursa na nameru odlaska iz organizacije: Medijatorska uloga organizacione posvećenosti. Ekonomski izazovi 10, (20): 96-114.

22.Jolović I., and N. Jolović. 2022. Human Resource Management Practices and Employee’s Job Withdrawal Intention in the COVID-19 Era: Job Satisfaction as a Mediator. In: A. Lošonc, A. Ivanišević (Eds.), Proceedings of the 8th International Scientific Conference “Socio-economic Aspects of the Pandemic: Crisis Management” (153-173). University of Novi Sad, Faculty of Technical Sciences, Novi Sad.

23.Jolović, I., and N. Jolović. 2023. The Linkage of Organizational Culture with Organizational Commitment: Prospects for Embedding a Sustainable Development Strategy at the Corporate Level. In: A. Lošonc, A. Ivanišević (Eds.), Proceedings of the 9th International Scientific Conference “Socio-economic Aspects of Development after the Pandemic” (129-151). University of Novi Sad, Faculty of Technical Sciences, Novi Sad.

24.Kelloway E. K., B. H. Gottlieb, and L. Barham. 1999. The Source, Nature, and Direction of Work and Family Conflict: A Longitudinal Investigation. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 4, (4): 337-346.

25.Kengatharan N. 2020. Too Many Big Fish in a Small Pond? The Nexus of Overqualification, Job Satisfaction, Job Search Behaviour and Leader-member Exchange. Management Research and Practice 12, (3): 33-44.

26.Lee X., B. Yang, and W. Li. 2017. The Influence Factors of Job Satisfaction and Its Relationship With Turnover Intention: Taking Early-career Employees as an Example. Annals of Psychology 33, (3): 697-707.

27.Li W., A. Xu, M. Lu, G. Lin, T. Wo, and X. Xi. 2020. Influence of Primary Health Care Physicians’ Perceived Overqualification on Turnover Intention in China. Quality Management in Healthcare 29, (3): 158-163.

28.Liu S., A. Luksyte, L. E. Zhou, J. Shi, and M. O. Wang. 2015. Overqualification and Counterproductive Work Behaviors: Examining a Moderated Mediation Model. Journal of Organizational Behavior 36, (2): 250-271.

29.Liu S., and M. Wang. 2012. Perceived Overqualification: A Review and Recommendations for Research and Practice. In: P. L. Perrewé, J. R. B. Halbesleben, C.

C. Rosen (Eds.), The Role of the Economic Crisis on Occupational Stress and Well Being: Research in Occupational Stress and Well Being (1-42). Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley.

30.Lobene E. V., A. W. Meade, and S. B. Pond. 2014. Perceived Overqualification: A Multi- source Investigation of Psychological Predisposition and Contextual Triggers. The Journal of Psychology 149, (7): 684-710.

31.Mah S., C. Huang, and S. Yun. 2024. Overqualified Employees’ Actual Turnover: The Role of Growth Dissatisfaction and the Contextual Effects of Age and Pay. Journal of Business and Psychology 39, (3): 1-19.

32.Mah S., Y. J. Shin, and Y. Min. 2024. Causal Relationship between Perceived Overqualification and Job Satisfaction, and Its Long-term Effects on Turnover: A Cross- lagged Analysis Across Four Years. Current Psychology 43, (17): 15925-15938.

33.Maltarich M. A., G. Reilly, and A. J. Nyberg. 2011. Objective and Subjective Overqualification: Distinctions, Relationships, and a Place for Each in the Literature. Industrial and Organizational Psychology 4, (2): 236-239.

34.Maynard D. C., and N. M. Parfyonova. 2013. Perceived Overqualification and Withdrawal Behaviours: Examining the Roles of Job Attitudes and Work Values. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 86, (3): 435-455.

35.Maynard D. C., T. A. Joseph, and A. M. Maynard. 2006. Underemployment, Job Attitudes, and Turnover Intentions. Journal of Organizational Behavior 27, (4): 509- 536.

36.Mobley W. H. 1977. Intermediate Linkages in the Relationship between Job Satisfaction and Employee Turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology 62, (2): 237-240.

37.Pan R., and Z. Hou. 2024. The Relationship between Objective Overqualification, Perceived Overqualification and Job Satisfaction: Employment Opportunity Matters. Personnel Review 53, (8): 1925-1949.

38.Parveen M., K. Maimani, and N. M. Kassim. 2017. Quality of Work Life: The Determinants of Job Satisfaction and Job Retention among RNs and OHPs. International Journal for Quality Research 11, (1): 173-194.

39.Piotrowska M. 2022. Job Attributes Affect the Relationship between Perceived Overqualification and Retention. Future Business Journal 8, (1): 1-29.

40.Ramalho Luz C. M. D., S. Luiz de Paula, and L. M. B. de Oliveira. 2018. Organizational Commitment, Job Satisfaction and their Possible Influences on Intent to Turnover. Revista de Gestão 25, (1): 84-101.

41.Rasheed R., A. H. Halawi, S. S. Hussainy, and A. Al Balushi. 2024. Perceived Overqualification and Turnover Intention in Nationalised Banks: Examining the Role of Employee Wellbeing. Evolutionary Studies in Imaginative Culture 8, (2): 580-593.

42.Rasheed R., M. Bhasi, A. H. Halawi, and B. A. M. Al Belushi. 2022. Turnover Intention among Overqualified Employees: A Multi Group Analysis and Its Implications. Journal of Positive School Psychology 6, (9): 3976-3993.

43.Ringle C. M., S. Wende, and J. M. Becker. 2022. SmartPLS 4. SmartPLS, Oststeinbek.

44.Scanlan J. N., and M. Still. 2019. Relationships between Burnout, Turnover Intention, Job Satisfaction, Job Demands and Job Resources for Mental Health Personnel in an Australian Mental Health Service. BMC Health Services Research 19, (1): 1-11.

45.Tian‐Foreman W. 2009. Job Satisfaction and Turnover in the Chinese Retail Industry.

Chinese Management Studies 3, (4): 356-378.

46.Tsui A. S., T. D. Egan, and C. A. O’Reilly III. 1992. Being Different: Relational Demography and Organizational Attachment. Administrative Science Quarterly 37, (4): 549-579.

47.Vinayak R., J. Bhatnagar, and M. N. Agarwal. 2021. When and How Does Perceived Overqualification Lead to Turnover Intention? A Moderated Mediation Model. Evidence-based HRM 9, (4): 374-390.

48.Wassermann M., K. Fujishiro, and A. Hoppe. 2017. The Effect of Perceived Overqualification on Job Satisfaction and Career Satisfaction among Immigrants: Does Host National Identity Matter? International Journal of Intercultural Relations 61, (1): 77-87.

49.Wong K. K. K. 2013. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Techniques Using SmartPLS. Marketing Bulletin 24, (1): 1-32.

50.Ye X., L. Li, and X. Tan. 2017. Organizational Support: Mechanisms to Affect Perceived Overqualification on Turnover Intentions: A Study of Chinese Repatriates in Multinational Enterprises. Employee Relations 39, (7): 918-934.

51.Yildiz B., F. Ozdemir, E. Habib, and N. Caki. 2017. The Moderating Effect of Collective Gratitude on the Overqualification–Turnover Intention Relationship. Journal of Organizational Behavior Research 2, (2): 40-61.

52.Zhang W., B. Xia, D. Derks, J. L. Pletzer, K. Breevaart, and X. Zhang. 2024. Perceived Overqualification, Counterproductive Work Behaviors and Withdrawal: A Moderated Mediation Model. Journal of Managerial Psychology 39, (5): 539-554.

Objavljeno u

God. 11 Br. 3 (2025)

Ključne reči

🛡️ Licenca i prava korišćenja

Ovaj rad je objavljen pod Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

Autori zadržavaju autorska prava nad svojim radom.

Dozvoljena je upotreba, distribucija i adaptacija rada, uključujući i u komercijalne svrhe, uz obavezno navođenje originalnog autora i izvora.

Zainteresovani za slična istraživanja?

Pregledaj sve članke i časopise