THE IMPACT OF PUBLIC EXPENDIRURE AND PUBLIC DEBT ON ECONOMIC GROWTH DECLINE

Abstract

This study analyzes the impact of public expenditure on economic growth in Southeast European countries, using data for Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Romania, Bulgaria, Albania, and Greece for the period from 2005 to 2021. The empirical analysis was conducted using Prais- Winsten regression with panel-corrected standard errors (PCSE) to correct for heteroskedasticity, autocorrelation, and cross-sectional dependence. The results show that an increase in public expenditure positively affects economic growth, while a high level of public debt negatively impacts growth. However, the interaction effect between public expenditure and high debt is not statistically significant, suggesting that public expenditure in countries with high debt does not have a pronounced negative effect on economic growth. These findings highlight the need for more careful consideration of fiscal policies in high-debt countries, particularly in the context of military expenditure.

Article

Introduction

The issue of public expenditure, viewed through military spending and its impact on economic growth, has become increasingly significant in contemporary economic analyses, particularly in countries with high public debt (Badmus and Okunola, 2017). The role of the state budget in the context of military spending presents a complex dilemma between preserving national security and maintaining economic stability (Kalaš and Milenković, 2021).

Given that public debt represents a burden on state finances, increasing military spending in countries with high debt levels can create additional fiscal pressure and slow down economic growth (Dunne, Nikolaidou, & Smith, 2002). In Southeast Europe, a region that has undergone intense political and economic transitions, military spending plays a key role in national policies, especially in the context of security challenges and international relations (Šare, 2024). Countries such as Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Romania, Bulgaria, Albania, and Greece face specific fiscal challenges, where high levels of public debt impose constraints on economic performance. These countries, although at different stages of economic transition, commonly grapple with the issue of how to balance military spending with the need for sustainable economic growth. These transitions have been accompanied by rising public debt and shifting fiscal policies, in which military spending has taken an important place.

Various factors, such as regional security challenges, NATO integration, and historical and political circumstances, have contributed to military budgets in these countries remaining a priority, even when economic conditions do not allow for significant increases in government expenditures (Løvereide, 2020). Previous research often highlights the dual role of military spending. Theoretical frameworks, such as Keynesian approaches to military spending, suggest that in the short term, military expenditure can boost aggregate demand and contribute to growth (Ceyhan & Kostekci, 2021).

On the other hand, approaches emphasizing the negative long-term consequences of high debt (Khan et al., 2020; Trifunović et al., 2023) point out that increasing military spending without corresponding revenue inflows can lead to fiscal imbalances (Durucan & Yeşil, 2022) and reduced investment in productive sectors (Aydin, 2021; Neševski & Bojičić, 2024; Penjišević, et al 2024). In this context, rising debt may cause increased interest rates, inflation (Friedman, 1970; Hartley, 2007), and reduced economic activity (Na & Bo, 2013; Barile et al., 2023; Trifunović, et al, 2024), particularly in countries with less developed economies (Gojković, et al., 2023). Advocates of this theory also argue that large investments in military spending reduce the capital available for economically more productive opportunities (Kentor & Kick, 2008).

This study analyzes how military spending in high-debt countries affects economic growth in Southeast Europe during the period from 2005 to 2021, taking into account the region’s specific economic characteristics (Korkomaz, 2015). The empirical analysis aims to provide insight into whether military spending in these countries stimulates or slows economic growth, with a special focus on the interaction between military spending and the level of public debt. Political stability also plays an important role in determining the funds allocated for defense in these countries (Elbargathi & Al-Assaf, 2023).

The question of whether increasing military spending contributes to fiscal instability and slows economic growth in high-debt countries poses a significant challenge for policymakers in the region. Understanding this relationship is crucial not only for shaping fiscal policy but also for the long-term prospects of sustainable development and stability in Southeast Europe. Using advanced econometric techniques such as Prais-Winsten regressions with panel-corrected standard errors (PCSE), this study will provide empirical insight into the relationship between military spending and growth, with a particular focus on public debt as a moderating factor.

Methodological Framework of the Research

This study investigates the impact of public spending, observed through military expenditures, on economic growth in Southeast European countries, which will be conducted by testing the following hypothesis:

H0: An increase in public spending, observed through military expenditures in Southeast European countries with high public debt, contributes to a reduction in economic growth.

To test this hypothesis, panel data covering the period from 2005 to 2021 were used for nine Southeast European countries: Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Romania, Bulgaria, Albania, and Greece.

The sample selection was made by choosing countries that share a similar level of economic-political development and geographical location. These countries share historical, political, and economic characteristics, making Southeast Europe a distinct region. All have undergone various forms of political and economic transitions, from wars to the process of European Union integration, which has significantly influenced their fiscal policies, including the level of public debt and military spending.

The period from 2005 to 2021 was chosen due to the stabilization of political and economic trends in the region following the turbulent 1990s. This period allows for a detailed examination of how fiscal and military policies have evolved in the post- conflict era and during the process of European integration.

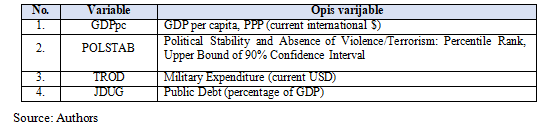

In the data collection process, a desk research method was employed, drawing from two secondary data sources: the annual report of the World Bank and the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). The research was conducted using econometric methodology within the scope of regression panel models, utilizing the STATA software package. Four variables were used in the empirical analysis:

Table 1. Variables used in the regression model

The variables listed in Table 1 will be used in the regression model where the dependent variable is GDPpc, while the independent variables are POLSTAB, TROD, and JDUG:

GDPpci= β0+ β1TRODi+ β2 JDUGi+ β3 POLSTABi+ui

The specified model will serve as the basis for applying econometric methods of panel data analysis to identify the effects of military spending on economic growth in the context of high public debt. Panel data is suitable for this type of analysis as it allows for the consideration of heterogeneities among countries, as well as changes over time (Marković & Nojković, 2012). The advantages of panel analysis include the ability to capture both time series and cross-sectional variability, thereby increasing the robustness and reliability of the results.

Data Analysis and Results

The data analysis revealed that the dataset is unbalanced, after which descriptive statistics were conducted for the variables used:

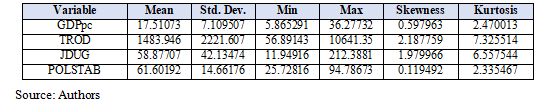

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of the variables used

These data provide insights into the central tendency, variability, skewness, and kurtosis of the distributions for each variable.

The mean value of GDP per capita growth is 17.51, with a standard deviation of 7.11, indicating significant variability among the countries during the analysis period. The minimum recorded value is 5.87, while the maximum is 36.28, suggesting that some countries experienced substantial growth, while others performed less favorably. The skewness of the distribution is 0.60, indicating a slight positive skew, where most countries have values below the average, but a few have significantly higher growth.

The kurtosis of 2.47 suggests that the GDPpc distribution is close to normal, with slightly fewer extreme values.

The average military expenditure as a percentage of GDP for the analyzed countries is 1483.95, with a very high standard deviation of 2221.61, indicating significant variability among countries in terms of military budget allocations. The minimum value is 56.89, while the maximum reaches 10,641.35, showing that some countries spend exceptionally large amounts on the military compared to others. The distribution's skewness is 2.19, indicating a high positive skew, where most countries spend below the average, but a few have significantly higher military expenditures. The kurtosis of 7.33 indicates the presence of extreme values, characteristic of one or a few countries allocating substantial resources to defense.

The mean public debt as a percentage of GDP is 58.88, with a standard deviation of 42.13, indicating considerable variability among the countries. The lowest recorded debt is 11.95, while the maximum reaches 212.39% of GDP, highlighting the serious indebtedness of certain countries. The skewness of the distribution is positive at 1.98, suggesting that most countries have debt levels below the average, but a few have exceptionally high debt levels. The kurtosis of 6.56 also points to the presence of extreme values, reflecting the high indebtedness of certain countries.

The average political stability in the analyzed countries is 61.60, with a standard deviation of 14.66, indicating a relatively stable political situation, though with variability among countries. The lowest recorded value is 25.73, while the maximum is 94.79, showing significant differences in political stability. The skewness of 0.12 indicates an almost symmetrical distribution, where values are evenly distributed around the mean. The kurtosis of 2.34 suggests that the distribution of political stability does not deviate significantly from normal.

Descriptive statistics clearly show significant variability among the countries regarding GDP growth, military spending, public debt, and political stability. It is particularly noticeable that military spending and public debt have high values of skewness and kurtosis, suggesting that a few countries have extremely high military expenditures and debt levels. These data provide important insights for further analyses, especially in the context of econometric models that will examine the effects of military spending on economic growth in Southeast European countries.

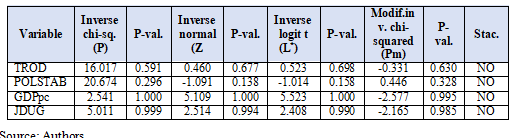

The next step in the analysis was to test the stationarity of the time series variables using the Fisher test (Dickey-Fuller tests), which is a first-generation unit root test. In this test, the null hypothesis is H0 – all panels contain a unit root, while the alternative is Ha – at least one panel is stationary.

Table 3. Results of the stationarity test for variables

Based on the results presented in Table 3, we can conclude that none of the variables are stationary, and it is necessary to differentiate the variables. After the differentiation of the variables, the stationarity check was performed again, confirming that all variables are now stationary.

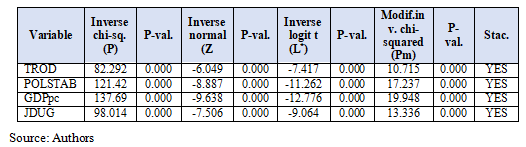

Table 4. Results of the stationarity test for differentiated variables

After the variables were brought to the same level of stationarity, a multicollinearity check was conducted on the panel data.

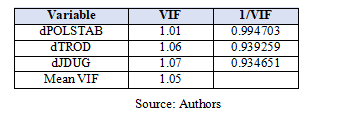

Table 6. Results of the Multicollinearity Check

It was determined that there is no multicollinearity. Such low multicollinearity (VIF

< 5) indicates that there is no significant linear dependence between the independent variables, meaning each independent variable is only weakly correlated with the other variables in the model. Furthermore, the estimated regression coefficients will be reliable, and the standard errors will not be inflated beyond what they should be.

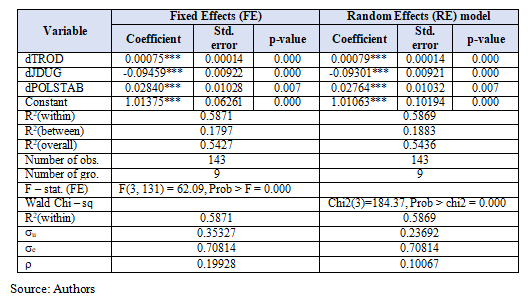

The next step in the analysis is to choose the appropriate model between the Fixed Effects (FE) model and the Random Effects (RE) model. First, we estimated the Fixed Effects (FE) model using the command xtreg (xtreg var1,..varn, fe), after which the obtained results were saved (estimate store fe). The same procedure was applied for the Random Effects (RE) model.

Table 6. Results of the Fixed and Random Effects Models

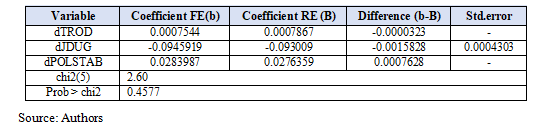

After obtaining the results for both models, the Hausman test was applied to assess which model is better for further analysis (hausman fe re), and the results are presented in the following table:

Table 7. Results of the Hausman Test

The null hypothesis of the Hausman test states that there is no correlation between the independent variables and the random effects (RE model), while the alternative hypothesis suggests that there is a correlation between the independent variables and the random effects (FE model). Based on the test results, with a Prob> chi2 of 0.4577 (< 0.05), we reject the null hypothesis and accept the alternative, indicating that the fixed effects model (FE) is more appropriate in our case.

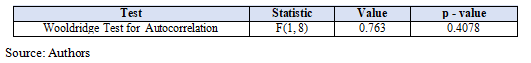

After selecting the model, we proceeded with testing it for the presence of heteroskedasticity, autocorrelation, and cross-sectional dependence among entities in the panel data. The first test was conducted to check for autocorrelation using the Wooldridge test, one of the most commonly used tests for detecting first-order autocorrelation in panel regressions.

Table 8. Results of the Autocorrelation Test

Given that the null hypothesis of this test states there is no autocorrelation, and the alternative hypothesis states there is first-order autocorrelation, we reject the null hypothesis and accept the alternative hypothesis of the presence of autocorrelation in our model, as the p-value result is 0.4078 (< 0.05).

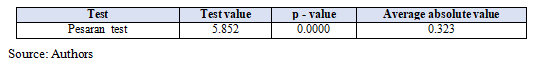

The next test performed was the Pesaran test (xtcsd, pasaran abs), which is used to test for cross-sectional dependence, i.e., whether changes in one entity affect changes in other entities.

Table 9. Results of the Cross-Sectional Dependence Test

The null hypothesis of this test states that there is no correlation between the residual errors across different units in the panel, while the alternative hypothesis suggests that there is correlation between the residual errors across different panel units. Given the test result with a p-value of 0.000 (< 0.05), we accept the alternative hypothesis indicating the presence of cross-sectional dependence.

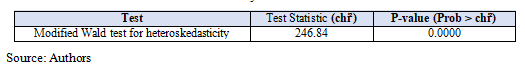

The final test conducted was the heteroskedasticity test, which was performed using the Modified Wald test (xttest3). The results are presented in the following table.

Table 10. Results of the Heteroskedasticity Test

The null hypothesis of this test states that the variance is constant (no heteroskedasticity), while the alternative hypothesis states that the variance is not constant (heteroskedasticity is present). Given the p-value result of 0.0000 (< 0.05), we reject the null hypothesis and accept the alternative hypothesis, confirming the presence of heteroskedasticity.

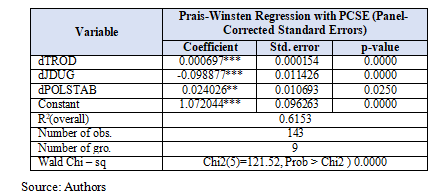

Since our model exhibits autocorrelation, heteroskedasticity, and cross-sectional dependence, we will use the Prais-Winsten method (xtpcse dGDPpc dTROD dJDUG dPOLSTAB, correlation(psar1)) for the final interpretation of the results, as it corrects for the previously mentioned issues and is also reliable when working with unbalanced panel data.

Table 11. Results of the Prais-Winsten Regression with PCSE

To test the given hypothesis of this research, "An increase in military spending in Southeast European countries with high public debt contributes to a reduction in economic growth," using the final model of the Prais-Winsten regression with PCSE, we will add an interaction between defense spending (dTROD) and a dummy variable indicating high debt. This will allow us to assess whether military spending has a different effect on economic growth in countries with high debt compared to countries with low debt.

After creating the dummy variable (gen visokJDUG=0), we classified all countries in years where their debt exceeded 60% (which is the standard according to the Maastricht criterion for EU countries) as high-debt countries (replace visokDUG=1 if dJDUG>60). Once we identified all the countries and years where debt exceeded 60%, we added the interaction effect between military spending (dTROD) and high debt (visokDUG) to our model.

dGDPpcit= β0+ β1dTRODit+ β2 visokDUGi + β3 (dTRODit ´ visokDUGit ) + β4dJDUGit+ β5dPOLSTABit+ui + eit

Where:

§ dGDPpcit the dependent variable representing the change in GDP per capita in the country i during year t.

§ dTRODit the change in military spending as a percentage of GDP in the country

i during year t.

§ visokDUGi a dummy variable indicating countries with high public debt (above

60% of GDP).

§ dTRODit ´ visokDUGit an interaction term that measures the effect of military spending in countries with high debt.

§ dJDUGit the change in the level of public debt in the country i during year t.

§ dPOLSTABit the change in political stability in the country i during year t.

§ ui are the time-invariant characteristics specific to each country (fixed effects).

§ eit the stochastic error specific to each country and time period.

Interpretation coefficients:

§ β1 : The effect of military spending on GDP in countries with low debt.

§ β2 : The effect of high public debt on GDP.

§ β3 : The effect of the interaction between military spending and high public debt

on GDP. This term is crucial for testing the hypothesis that military spending in high-debt countries negatively impacts economic growth.

§ β4 : The effect of changes in public debt on economic growth.

§ β5 : The effect of political stability on economic growth.

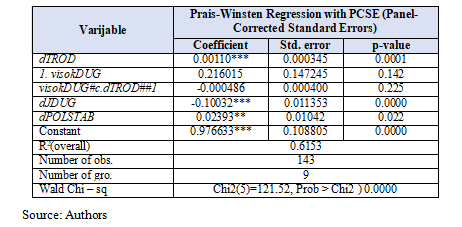

When we applied the Prais-Winsten regression with PCSE (xtpcse dGDPpc c.dTROD##i.visokDUG dJDUG dPOLSTAB, correlation(psar1)), we obtained the following result:

Table 12. Results of the Prais-Winsten Regression with PCSE, including the interaction effect

The coefficient for defense spending is positive and statistically significant at the 1% level (p < 0.01). This means that, on average, an increase in military spending by 1 unit (as a percentage of GDP) has a positive impact on the GDP per capita growth rate in the analyzed Southeast European countries. This finding suggests that military spending, by itself, can have a stimulative effect on economic growth.

The coefficient for high debt (visokDUG) is not statistically significant (p > 0.1), meaning that a high level of public debt does not show a significant direct effect on economic growth. In this model, countries with high debt do not significantly differ in terms of economic growth compared to countries with lower debt levels.

Although the interaction coefficient between military spending and high debt is negative, which would suggest that military spending in high-debt countries reduces economic growth, this coefficient is not statistically significant (p > 0.1). Therefore, there is not enough evidence to suggest that military spending in high-debt countries significantly negatively affects economic growth. The coefficient for dJDUG is negative and highly statistically significant (p < 0.01). This means that an increase in public debt negatively affects economic growth. Every 1% increase in debt as a percentage of GDP reduces the GDP per capita growth rate. This aligns with theoretical expectations that rising public debt burdens fiscal stability and slows down the economy. The coefficient for dPOLSTAB is positive and statistically significant at the 5% level (p < 0.05), indicating that greater political stability positively impacts economic growth. An increase in the political stability index by 1 unit leads to an increase in GDP per capita growth.

Discussion

The research results suggest that military spending in Southeast European countries positively impacts economic growth in general, while an increase in public debt significantly negatively affects GDP growth. These findings align with some of the literature indicating that military spending can have positive effects on economic growth, particularly in the short term, through increased aggregate demand and stimulation of certain economic sectors (Dunne et al., 2002). The literature often emphasizes that military spending can have a stimulative effect in economies facing recession or slow growth, which is partially reflected in the results of this research.

However, the finding that military spending does not have a significantly negative effect in countries with high debt differs from some of the literature, which indicates that increasing military spending in countries with fiscal constraints can further exacerbate economic growth. Studies such as those by Knight, Loayza, and Villanueva (1996) suggest that high military spending combined with high public debt can divert resources away from productive sectors, negatively affecting long- term growth. In this research, the interaction between military spending and high debt is not statistically significant, indicating that military spending does not contribute to significant growth slowdowns in the context of high public debt.

Furthermore, the finding that increasing public debt significantly negatively affects economic growth is entirely consistent with numerous studies that show high public debt reduces fiscal space and threatens growth sustainability (Reinhart and Rogoff, 2010). This result clearly shows that countries with rising debt need to carefully balance their fiscal policies, especially in the context of military spending.

The theoretical contribution of this paper lies in further clarifying the relationship between military spending and economic growth in Southeast European countries, with particular attention to the role of public debt. While there are numerous studies examining the effect of military spending on growth in a global context, there are few that focus on the specific region of Southeast Europe, characterized by high levels of public debt and specific geopolitical challenges. This paper contributes to the literature by showing that military spending does not play a negative role in high- debt economies in this region, contrary to some global findings.

Additionally, the results emphasize the importance of political stability as a factor that positively influences economic growth. The literature often highlights the connection between political stability and economic progress, but few studies have included political stability as a key variable in the analysis of military spending and growth. This paper shows that political stability can mitigate the negative effects of fiscal burdens and contribute to sustainable growth, opening new space for discussions on long-term economic stability strategies in the region.

The practical implications of this research are significant for policymakers in Southeast European countries. First, the results suggest that military spending, in itself, does not necessarily slow economic growth, even in countries with high debt. This could be important for countries balancing between fiscal constraints and geopolitical demands for higher defense spending, such as Greece, Romania, and Serbia. Policymakers in these countries may consider military spending as an instrument for short-term economic stimulation but must be cautious not to increase public debt to levels that could jeopardize long-term growth.

Second, the negative impact of public debt on growth highlights the need for stricter fiscal discipline in high-debt countries. Policymakers should align their fiscal strategies with sustainable development goals, including rationalizing military expenditures and redirecting resources toward productive investments with greater potential for stimulating long-term growth.

Finally, the finding on the significance of political stability provides further insight into how a stable political environment can support economic growth. For Southeast European countries, which often face political instability, ensuring political stability can be a key strategy for achieving sustainable economic progress. Policymakers should work on improving institutional efficiency and reducing political tensions to support long-term growth.

Conslusion

This research provides significant insights into the impact of public spending, observed through military expenditures, and public debt on economic growth in Southeast European countries. The findings show that military spending has a positive and statistically significant effect on economic growth, suggesting that military allocations can stimulate the economy, particularly in the short term. This is consistent with the theory that increased military spending can boost aggregate demand, which may benefit economic growth under certain conditions. On the other hand, the results clearly indicate that an increase in public debt significantly negatively affects economic growth, confirming the importance of fiscal discipline in maintaining economic stability.

One of the key aspects of this study was the interaction between military spending and high public debt. Although the coefficient for this interaction was negative, which could suggest that military spending in high-debt countries reduces economic growth, the results were not statistically significant. This indicates that the increase in military spending in high-debt countries did not show a significant negative effect on growth during the analyzed period. This finding contrasts with some previous studies suggesting that military spending could further burden economies in high- debt countries.

Additionally, the research shows that political stability has a positive effect on economic growth, highlighting the importance of a stable political environment for economic progress. This result is consistent with expectations, as political stability creates a favorable environment for investment and economic development.

However, this research has certain limitations. First, the time span of the analysis covers the period from 2005 to 2021. While this is a substantial timeframe, future research could deepen the analysis by exploring longer-term trends to capture broader effects of military spending and fiscal policies. Second, the availability and quality of data on public debt, political stability, and military spending vary across countries, which may affect the precision of the results.

Future studies could include a deeper analysis of the structure of military spending to examine how different aspects of defense expenditures impact economic growth. Additionally, geopolitical factors and the foreign policy context could provide further insight into the dynamics of military spending and its impact on economic growth. Further research with a longer time horizon would allow for an examination of the long-term effects of military expenditures. Comparative studies involving other regions, such as Western Europe or the Middle East, could deepen the understanding of the specific impacts of military spending on economic growth in different geopolitical contexts.

This research emphasizes the importance of carefully balancing fiscal policy and military expenditures in Southeast European countries. While military spending may have a positive short-term effect on economic growth, rising public debt clearly slows economic progress. The practical implications of this research are significant for policymakers, who must consider the sustainability of fiscal policies in the context of military and economic priorities. Future studies could expand on these findings and provide additional guidance for policymaking in the region.

References

2.Badmus, B., i Okunola, A. 2017. Military expenditure versus structural adjustment programme: Implication and alternatives. Afro Asian Journal of Social Studies: 1-15.

3.Barile, D., Pontrelli, V., & Posa, M. (2023). How can I fund you? A cross- cultural analysis on the diffusion of reward-based crowdfunding activities. Društveni horizonti (Social Horizons), 3(6).

4.Ceyhan, T., i Kostekci A. (2021). The effect of military expenditures on economic growth and unemployment: Evidence from Turkey. Fırat Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 31(2): 913-928.

5.Dunne, J. P., E. Nikolaidou, and R. Smith. 2002. "Military Spending, Investment, and Economic Growth in Small Industrialising Economies." South African Journal of Economics 70, no. 5: 789-790.

6.Durucan, A,. i Yeşil, E. 2022. “The Impact of Defence Expenditures on Government Debt, Budget Deficit, and Current Account Deficit: Evidence from Developed and Developing Countries”, Eskişehir Osmangazi Üniversitesi İİBF Dergisi, 17(3): 686-701.

7.Friedman, M. 1970. "The Counter-Revolution in Monetary Theory." IEA Occasional Paper No. 33.

8.Gojković, B., Obradović, Lj. & Mihajlović, M. (2023). The influence of macroeconomic factors on the public debt of the Republic of Serbia in the post- transition period. Akcionarstvo, 29(1), 217-238

9.Hartley, K. 2007. Defense economics: achievements and challenges, The Economics of Peace and Security Journal, ISSN 1749-852X, 2(1): 45-50.

10.Kalaš, B., Mirović, V. i Milenković N. 2021. Panel cointegration analysis of military expenditure and economic growth in the selected Balkan countries, Ekonomske teme, 59(3): 375-390.

11.Kentor, J., i Kick, E. 2008. Bringing the Military Back in: Military Expenditures and Economic Growth 1990 to 2003. Journal of World-Systems Research, 14(2): 142–172. https://doi.org/10.5195/jwsr.2008.342.

12.Khan, L., Arif, I. i Waqar, S. 2020. The Impact of Military Expenditure on External Debt: The Case of 35 Arms Importing Countries, Defence and Peace Economics: 31(2), https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2020.17232 39.

13.Knight, M., Loayza, N., i Villanueva, D. 1996. The Peace Dividend: Military Spending Cuts and Economic Growth, IMF Staff Papers, 43(1): 1-37.

14.Korkmaz, S. 2015. The Effect of Military Spending on Economic Growth and Unemployment in Mediterranean Countries, International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 5(1): 273-280.

15.Løvereide, M. 2020. Military Expenditure and Economic Growth, Defence and Peace Economics, 20(4): 327-339.

16.Marković, Z., i Nojković A. 2012. Primenjena analiza vremenskih serija. Centar za izdavačku delatnost Ekonomskog fakulteta u Beogradu.

17.Na, H., i Bo, C. 2013. Military expenditure and economic growth in developing countries: evidence from system GMM estimates, Defence and Peace Economics, 24(3): 183-193, DOI: 10.1080/10242694.2021. 710813.

18.Neševski, A. & Bojičić, R. (2024). Analiza uloge sopstvenih prihoda u finansiranju rashoda. Akcionarstvo, 30(1), 95-112

19.Penjišević, A., Somborac, B., Anufrijev, A. & Aničić, D. (2024). Achieved results and perspectives for further development of small and medium-sized enterprises: statistical findings and analysis. Oditor, 10 (2), 313-329.

20.Reinhart, Carmen M., and Kenneth S. Rogoff. 2010. "Growth in a Time of Debt." American Economic Review, 100 (2): 573–78.

21.Šare, D. 2024. Uticaj odabranih društveno-ekonomskih faktora na troškove odabrane u zemljama Jugoistočne Evrope. Ekonomija: teorija i praksa. 17( 2): 1-22.

22.Trifunović, D., Bulut Bogdanović, I., Tankosić, M., Lalić, G., & Nestorović, M. (2023). Research in the use of social networks in business operations. Akcionarstvo, 29(1), 39–63.

23.Trifunović, D., Lalić, G., Deđanski, S., Nestorović, M., & Bevanda, V. (2024). Inovativni modeli i nove tehnologije u funkciji razvoja i kooperacije preduzeća i obrazovanja. Akcionarstvo, 30(1), 177–196.

Published in

Vol. 11 No. 3 (2025)

Keywords

🛡️ Licence and usage rights

This work is published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

Authors retain copyright over their work.

Use, distribution, and adaptation of the work, including commercial use, is permitted with clear attribution to the original author and source.

Interested in Similar Research?

Browse All Articles and Journals