ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF SERBIA AFTER 200 0– RESULTS AND PERSPECTIVES FOR DEVELOPMENT

Abstract

The economic development of Serbia is largely based on traditional sectors (food industry, agriculture, construction, metal industry) characterized by low productivity and limited added value, employing over 50% of the total workforce. Consequently, Serbia has failed to reduce its development gap relative to the Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries over the past 20 years and remains at 60% of their average level. Achieved growth rates have primarily relied on increased investments and employment, with minimal contributions from technical progress and new technologies. Therefore, a shift in economic policy is necessary, emphasizing the application of knowledge and new technologies, along with significantly higher investment participation in the gross domestic product (GDP) from the domestic private sector. Only growth based on these assumptions will be sustainable in the long term and lead to increased competitiveness of the economy in the global market.

Article

Introduction

At the beginning of the 2000s, Serbia faced a significant economic lag compared to the countries of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), particularly when measured against developed nations of the European Union. This economic underdevelopment was primarily the result of hyperinflation during the 1990s, international sanctions imposed by the global community and the 1999 NATO bombing. Following political changes in 2000, Serbia reopened to international cooperation and initiated a privatization process, which further weakened its economic structure, particularly through the dismantling of its industrial sector as the backbone of the economy. The country’s economic policy largely relied on foreign direct investments (FDIs) and public infrastructure development, while neglecting domestic private investments, resulting in a persistent gap in development compared to the developed world.

In recent years, Serbia has achieved a moderate level of economic development, with growth and development primarily driven by increases in capital and employment, particularly in traditional sectors. The immediate determinants of economic growth include investments, employment and technological progress, supplemented by the broader economic environment characterized by macroeconomic stability (exchange rate stability, inflation control, tax policy, interest rates and infrastructure). Serbia's economy remains dominated by traditional sectors (construction, food processing, rubber manufacturing, metallurgy, agriculture and mining), which exhibit low productivity and limited added value, employing more than 50% of the workforce. Consequently, Serbia has failed to reduce the development gap with CEE countries over the past two decades and currently stands at 60% of their average development level.

This paper analyzes the growth of Serbia's gross domestic product (GDP) and investments in the period following 2000, as well as the growth trends of these indicators in CEE countries and the global average. Primary aim is to determine, through comparative analysis, whether Serbia has managed to reduce its developmental lag relative to CEE countries, considering that in the 1980s, Serbia outperformed this group of countries in several economic development indicators. Based on the findings, recommendations can be provided to economic policymakers to address and rectify policy missteps that have occurred since 2000.

Methodology

The defined subject and objectives of the research have determined the application of both qualitative and quantitative methodologies. Qualitative research has enabled an overview of scientific achievements related to the observed issue and facilitated necessary comparisons. The empirical research was conducted based on secondary data from relevant domestic and international sources, including textbooks from economics and related faculties, scientific journals, and statistical data published by domestic and foreign institutions related to economic development.

The analytical method was used to identify the fundamental indicators and factors of economic development, as well as to provide their theoretical and empirical coverage and measurement. The synthetic method was applied to integrate key elements of economic development into a unified whole, allowing for the derivation of relevant conclusions. This method was also employed to connect individual indicators of GDP growth and other macroeconomic variables into a comprehensive system from which aggregated indicators and conclusions could be drawn.

A comparative method was used to analyze Serbia’s GDP growth rates relative to Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries and the global average over two separate periods: 2001–2011 and 2012–2023. Additionally, gross investment rates in Serbia, CEE countries, and the global average were compared for the same periods. The comparative analysis led to the conclusion that Serbia's economic development is still predominantly based on traditional sectors with low productivity and limited added value, in contrast to CEE countries, where innovation-driven and high-tech sectors are more prevalent.

The historical method was applied to chronologically present Serbia's economic development alongside CEE countries from 2000 to the present, using data from relevant databases such as the World Bank. Furthermore, historical data on Serbia’s and CEE countries’ economic development before and after 2000 were analyzed. The findings indicate that Serbia currently stands at 60% of the development level of CEE countries, whereas before the 1990s, it was more developed than them.

The descriptive method was utilized to present relevant indicators of economic growth and development, along with factors influencing economic policy. The compilation method was employed to integrate the findings of empirical research and scientific studies conducted by other authors who have examined similar topics.

Literature Review

Economic growth is a measurable, numerically expressed component of development that represents the aggregate economic value of goods and services produced within a given time period (Madžar, 2002). In addition to economic growth, economic development encompasses structural changes in the economy and, accordingly, represents a process of overcoming economic backwardness (Djurić-Kuzmanović, 2001). Economic development involves an increase in national economic output while also explaining complex transformations in the composition and structure of the economy, as well as changes in the significance and contribution of various inputs to overall output growth (Rosić, 2002).

The significance of economic growth is reflected in its contribution to the overall prosperity of society. Growth enables an increase in the consumption of goods and services, as well as improvements in the quantity and quality of public goods and services, thereby raising the standard of living within a society. Therefore, increasing the rate of economic growth and development remains one of the primary objectives of macroeconomic policy (Kitanović et al., 2008).

Economic development is not merely an economic phenomenon. Ultimately, it must encompass more than the material and financial aspects of human life. It should be understood as a multidimensional process that, in addition to increasing material production, entails a reorganization of the entire economic and social system (Cvetanović, 2004).

Economic development should not be perceived as a linear, historically determined, and constantly recurring trend. Instead, it should be regarded as a process characterized by continuous positive and negative deviations around a certain equilibrium growth trend. Development is considered sustainable if it meets the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (Pokrajac, 2002). Sustainable development, beyond its economic and environmental dimensions, must also be socially, culturally, and politically viable. Global markets and global technologies have the potential to enrich human lives in every corner of the world and significantly expand the range of choices available to individuals (Jovanović Gavrilović, 2005).

New Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) create opportunities for economic growth, development, improved healthcare, better services, and overall social and cultural advancement (Ilić, 2005). Increases in production and services, and consequently GDP growth, can occur even without additional investments, thanks to technological progress and better utilization of existing resources (Bajec & Joksimović, 2004).

The most significant sources of economic growth include the size and quality of the labor force, the quality of capital (research and development, technology transfer, innovation), and improvements in the efficiency of combining labor and capital in production (Vukotić, 2001). The importance of natural resources for a country's economy is determined by its level of economic and technological development, the characteristics of its economic structure, the position of the national economy within the international division of labor, and a range of strategic and political factors that shape the country’s development orientation (Aranđelović, 2004).

Globalization is often presented as a qualitatively new stage in the development of the world economy, characterized by the dominance of transnational corporations, financial capital, and the consequent redistribution of economic and political functions between nation-states, transnational corporations, and international organizations (Leković, 2008). Without delving into the political aspects of globalization, it can be concluded that it is a long-term economic trend that should not be resisted, as modern society is inherently characterized by processes of interconnection, internationalism, and global integration (Veselinović, 2006).

Beck (2003) defines globalization as a process through which transnational actors with different power prospects, orientations, identities, and networks intersect sovereign nation-states. Globalization represents an unstoppable process, and any state that opposes its manifestation would be condemned to political isolation and economic stagnation (Mesarić, 2002). In the globalization process, the rules of the game are dictated by the large and powerful, making autocracy appear as the only alternative to globalization. Regardless of whether globalization is beneficial for some and detrimental for others, isolation is undoubtedly the worst possible outcome, meaning it should never be considered an alternative to globalization (Drašković, 2003).

Serbia’s transition began with a decade-long delay, during which the initial advantages the country had over other post-socialist economies were lost. The advantage of entering the transition later and learning from the experiences of others was squandered, ultimately affecting the balance of achieved results (Jovanović Gavrilović, 2010). Serbia’s industry lags significantly behind other transition economies. The technological structure of the industry has not substantially changed, and it remains dominated by low-tech and medium-low- tech subsectors. The services sector has a disproportionately large share in GDP creation and contributes the most to its growth (Ministry of Finance, 2011).

Serbia is too poor relative to its production potential. Consequently, the country should focus on developing industrial production—particularly in the machinery and automotive industries, as well as the broader chemical industry—to achieve competitiveness in foreign markets (Hausmann et al., 2009).

Economic policy can have both positive and negative effects on structural changes in the economy, either bringing it closer to or pushing it further away from its optimal state (Marjanović, 2015). Therefore, a state's ability to shape and influence the structure of the economy and individual sectors through appropriate economic policies is crucial. It must efficiently, continuously, and actively implement structural changes in accordance with the available development factors (Mićić, 2016).

In developing countries, structural changes are essential to ensure faster progress toward higher levels of development (Lin, 2012) and to reach countries with a higher GDP per capita. Today, in addition to the main drivers of structural change—innovation and new technologies—factors such as knowledge, investment, externalities, skills, resource utilization, supply and demand, international trade, connectivity and agglomerations, institutional frameworks, and globalization play a significant role (UNIDO, 2013).

Deindustrialization leads to the tertiarization of the economic structure due to the strong development of the service sector. This is a long-term process that varies to some extent between countries (Timmer, Akkus, 2008). A common characteristic of this process is the correlation between GDP per capita, sectoral contributions to GDP, value added, employment distribution, and labor productivity.

In endogenous growth theories, technology plays a central role in explaining economic development and structural change (Baldwin, Braconier & Forslid, 2005). These theories also examine the role of research and development, infrastructure, government, institutional factors, and organizations. Furthermore, they incorporate intangible factors such as organizational structure, managerial capabilities, and culture in explaining development and structural transformations.

GDP Growth in CEE Countries and Serbia from 2000 to 2024

Serbia has achieved a moderate level of economic development, with growth driven primarily by increased capital and employment in traditional sectors. However, to achieve further growth and join the ranks of high-income developed countries, a shift toward high-tech industries is essential. These are sectors with high added value, capable of attracting young, highly skilled labor to remain in the country and contribute to its development.

Immediate determinants of economic growth include investment rate, employment and technological progress, while additional factors encompass economic environment, such as macroeconomic stability (exchange rate stability, inflation control, tax policy, interest rates, and infrastructure). Fundamental growth factors include geographic attributes, historical heritage, culture and institutions (Arsić, 2024).

Serbia’s economy is dominated by traditional sectors, such as construction, food processing, rubber manufacturing, metallurgy, agriculture and mining, which exhibit low productivity and limited added value, employing over 50% of the workforce. As a result, Serbia has failed to narrow the development gap with CEE countries over the past two decades, remaining at 60% of their average development level (Petrović, 2024). In contrast, countries like Croatia, Romania and Bulgaria have reached approximately 90% of the CEE average.

Serbia's GDP growth has been driven by increased employment, capital accumulation and some technological progress. High growth rate has primarily been the result of increased investments and employment, with minimal contributions from technological advancements, contrary to the CEE growth model, where technological progress serves as the primary driver. Investment and employment-based growth model is gradually becoming unsustainable due to unfavorable demographic trends.

Economic growth in Serbia has predominantly been fueled by investments, which in recent years have exceeded 20% of GDP. However, two-thirds of these investments have been initiated by the state through public institutions and enterprises, while foreign investors accounted for one-third. Domestic private enterprises have not contributed to this investment growth; their investments have declined, highlighting a significant structural imbalance. This raises the question of whether Serbia can sustain its current growth trajectory (Petrović, 2024). Domestic investments are largely concentrated in traditional sectors, reflecting a reluctance among investors to engage in riskier, high-tech projects that are prevalent in technologically advanced economies. Future growth must be based on the adoption of new technologies by domestic private sector, which requires an appropriate environment, including strong institutions, the rule of law and focus on education.

Investments represent a crucial immediate factor in economic growth, as their level and efficiency reflect the quality of economic policy and institutional frameworks. Investments also influence other drivers of economic growth, such as technological progress and employment. The impact of investments on economic growth depends on numerous factors, including macroeconomic and institutional environment, the openness of the economy, the intensity of competition and others. According to Levin and Renelt (1992), investments and economic openness are the most significant drivers of economic growth, while Mankiw et al. (1992) estimate that investments in physical capital account for approximately one-third of economic growth.

Three groups of factors determine differences in investment efficiency across countries. Institutions: these include the protection of property rights and equal treatment of market participants. Structural Characteristics of the Economy: this encompasses the development of financial system, the openness of economic system, demographic characteristics of the population and similar factors. Economic Policy: this includes tax policy, inflation levels, public debt, wage dynamics, productivity and other related elements (Besley, 1995; Lim, 2014).

The most successful episodes of high GDP growth rates and economic convergence with developed countries in recent decades—such as Italy (1960– 1980), Spain (1980–2009), Japan (1966–1997), South Korea (1988–2010) and

Taiwan (1968–2008)—were primarily based on several common characteristics (Šoškić, 2024):

· Ambitious initial reform packages,

· Productivity growth,

· A significant increase in the share of investments in GDP and

· Development of financial system.

Economic development consists of two primary components: 1) Economic Growth and 2) Structural Changes in the Economy (Devetaković et al., 2010). Factors influencing economic development can be categorized into: 1. Basic or Primary Factors - these include population and its structure, the level and availability of natural resources and the size of the country; 2. Systemic Factors - these refer to the dominant forms of ownership, decision-making systems and coordination and management mechanisms; 3. Effects of Economic and Development Policies - these include policy interventions that shape economic performance and long-term development trajectories (Dragutinović et al., 2012).

One of the most critical missing factors explaining the poor performance of underdeveloped countries is social infrastructure. Social infrastructure includes "soft" factors that facilitate economic interactions, thereby enhancing the efficiency of all other factors. These factors encompass property rights, human rights and the rule of law. Additionally, public infrastructure serves as a key determinant that raises the production function, ceteris paribus (Burda & Wyplosz, 2012).

The most commonly used indicator of a country's economic performance is economic growth, measured by the increase in real GDP or real GDP per capita over a specific period. A growing economy signifies an increasing number of jobs, greater capacity to finance the public sector and improved population welfare. Economic efficiency refers to the effectiveness with which an economic system utilizes available resources (including knowledge) either in a specific period (static efficiency) or over time (dynamic efficiency) (Gregory & Stuart, 2015).

Structural changes significantly influence the design and implementation of economic policy, which represents the deliberate effort by the state to achieve specific development objectives. Economic policy can either positively or negatively impact changes in the economic structure, steering it closer to or further away from its optimal configuration (Marjanović, 2015, p. 67). Therefore, it is crucial for the state to possess the capacity to shape and influence the economy’s structure and the composition of individual sectors through appropriate economic policies. This requires effectively, continuously and proactively implementing structural changes in alignment with the available development factors (Mićić, 2016, pp. 153–161).

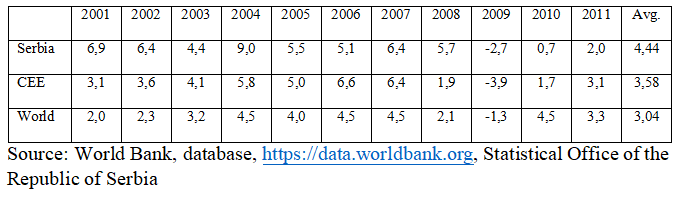

Data from Table 1 indicate that Serbia has achieved a higher average GDP growth rate compared to the average of CEE countries and the global average. However, it is important to consider that Serbia started from a very low baseline at the beginning of the 2000s. This low baseline was a direct consequence of the events during the 1990s, including international sanctions imposed by the UN Security Council, hyperinflation in 1992/93 and the 1999 NATO bombing. These factors left the Serbian economy severely devastated and disconnected from global economic flows.

Table 1: GDP in Serbia, CEE and World from 2001 to 2011, annual growth rates in %

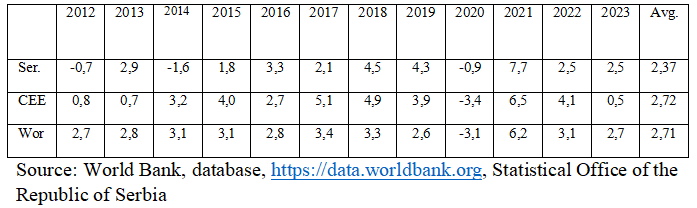

Since 2012, Serbia’s average GDP growth rate has fallen below the average of Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries and the global average (Table 2). This period was marked by two major global events that significantly impacted the economies of all nations: the 2008 global economic and financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Both events resulted in substantial reductions in economic activity worldwide. However, some countries suffered less due to the resilience and adaptability of their economies to external shocks.

For Serbia, the economic trajectory post-2000 was notably shaped by the privatization of state-owned enterprises. This process had significant effects on the country's development path. Privatization effectively became a process of deindustrialization, as buyers of production enterprises were not obligated to continue operations. A considerable portion of enterprise acquisitions was motivated by the favorable locations of these properties, with plans to repurpose them for commercial and residential real estate development in the future. This led to numerous negative consequences, including: a decline in GDP, increased unemployment and a decrease in the population’s standard of living. Additionally, Serbia consistently faced a negative trade balance, characterized by higher imports than exports. The country’s external debt has also shown a continuous upward trend over the years.

Table 2: GDP in Serbia, CEE and World from 2012 to 2023, annual growth rates in %

Investment Policy as a Driver of Economic Development

Investments are one of the key drivers of economic growth, with their efficiency reflecting the quality of a country’s economic policies and institutions. Investments also impact other factors of economic growth, such as technological progress and employment. Differences in investment efficiency play a crucial role in determining the level of economic development among countries. The challenges of rational investment—efficient planning and execution of appropriate investment projects—are among the critical issues in economic development, as investment failures can have significant negative macroeconomic consequences. Macroeconomic policy must create a favorable investment climate to encourage domestic and foreign investments, thereby promoting overall economic and social development.

The efficiency of investments varies between countries depending on the quality of institutions, the structure of the economy and the policies implemented. In addition to foreign investments, domestic public and private investments play a crucial role in economic development, as demonstrated empirically in many developed countries. Foreign direct investments (FDIs) can have numerous positive effects on the host country but may also bring negative consequences, particularly for economies overly reliant on them. This is especially true for FDIs that are primarily attracted by cheap labor and significant tax incentives or subsidies.

Beyond domestic savings, other factors influence the level of investments, including macroeconomic policies, institutional quality and economic structure. Economic policy positively affects private investments if it maintains macroeconomic stability, characterized by low inflation, stable exchange rates, low and relatively stable interest rates and the absence of risks related to public or private debt crises (Aizenman & Nancy, 1993). Fatas & Mihov (2013) argue that investment policy benefits more from consistent economic rules rather than discretionary government decisions. A stable and predictable policy framework enhances investor confidence, reduces uncertainty and fosters sustained economic growth.

Empirical studies have demonstrated that countries with higher domestic savings achieve greater investment levels and faster economic growth. Feldstein & Horioka (1981) established that differences in investment rates among countries closely correlate with differences in domestic savings rates. Similarly, Aizenman et al. (2007) found that developing countries finance approximately 90% of their capital investments through domestic savings. These studies also highlight that economies relying more on domestic savings for investment financing experience higher economic growth. High levels of domestic savings reflect strong institutions, a favorable business environment and sound economic policies. Aghion et al. (2006) underscore the importance of domestic savings in developing countries, emphasizing that it facilitates the adoption of advanced technologies critical for economic modernization.

Developing economies often base their growth strategies on foreign direct investments (FDIs), which provide various advantages: access to advanced technologies unavailable domestically, integration into international markets (particularly through global multinational corporations), and improvements in managerial practices and workplace discipline (Filipović & Nikolić, 2017).

However, insufficient total investments negatively impact labor productivity, employment and future real wages, fostering emigration trends. To boost total investments, it is essential to increase productive public investments and use economic policy to create systemic incentives for both savings and investments.

In Serbia's transition period, FDIs were predominantly realized through privatization rather than greenfield investments, leading to less transformative effects on the economy (Maksimović & Kostić, 2019).

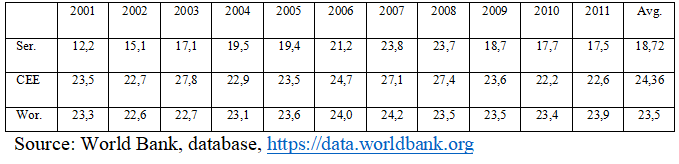

Data from Table 3 reveal that investment rates in Serbia from 2001 to 2011 were significantly lower than the average for Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries and the global average. This disparity has substantially influenced Serbia's GDP trends compared to peer economies.

Table 3: Gross investments in Serbia, CEE and World from 2001 to 2011, as a part of GDP in %

In Serbia, there are frequent changes in economic policy, with a large number of laws being passed through expedited procedures, often without necessary public consultations. This creates uncertainty in business operations and increases risks, which negatively affects investment decisions. Furthermore, an important cause of low domestic investments in Serbia is weak institutions. These institutions create so-called non-commercial risks, such as weak protection of property rights, frequent changes in regulations and similar factors. Characteristics of weak institutions include complicated bureaucratic procedures, high levels of corruption, a large informal economy and unequal treatment of investors, all of which contribute to increased investment costs and, consequently, a lower volume of investments. In such an environment, investors are forced to spend a significant portion of their time and resources on non-productive activities, such as lobbying, which results in a reduction of resources available for investment.

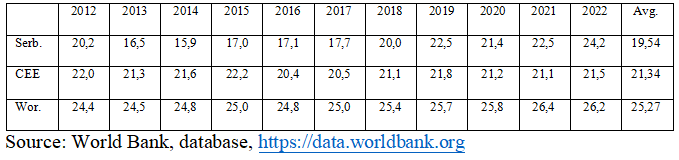

After 2011, Serbia saw a gradual increase in the investment-to-GDP ratio, which for the period 2012-2023 was 19.54%, approaching the CEE average of 21.34%, but still significantly lower than the global average of 25.27%. Since 2019, Serbia's investment rate has been higher than the CEE countries, but it is still insufficient to significantly reduce the development gap. Economic literature suggests that Serbia would need an investment rate of at least 25% of GDP to catch up with the developed world. A key factor in achieving sustainable growth is the sectoral structure of investments, particularly a higher share of domestic private investments in total investments. A greater role for domestic investment would significantly increase the competitiveness of the domestic economy and create the basis for long-term sustainable development in the global market.

Table 4: Gross investments in Serbia, CEE and World from 2012 to 2023, as a part of GDP in %

Conclusion

Frequent changes in economic policy are characteristic of Serbia, creating uncertainty in business operations, increasing business risks and negatively impacting investment decisions. A major cause of low domestic investment in Serbia is weak institutions, which create so-called non-commercial risks, such as weak protection of property and contract rights, frequent changes in regulations and similar issues. Economic literature suggests that Serbia needs to achieve an investment rate of at least 25% to catch up with the developed world. The sectoral structure of investments is also crucial, particularly the increased participation of domestic private investments in total investments. This would significantly enhance the competitiveness of domestic economy and create the conditions for long-term sustainable development in the global market.

Investments represent one of the key elements of economic policy, as their implementation creates the conditions not only for economic development but also for the stability of economic and social flows. Less developed countries, such as Serbia, should base their economic development, among other things, on structural adjustment through increased investments. The economic structure of investments determines the productive structure of the national economy, imports, exports, employment and other key macroeconomic indicators. Therefore, ensuring a favorable investment climate is an important part of developmental economic policy, which includes a sound legislative framework, an efficient and non-corrupt judiciary, minimal bureaucratic obstacles to investments, good physical infrastructure, skilled and qualified workforce.

References

2.Aizenman, J., Nancy, M., (1993) Policy Uncertainty, Persistence and Growth, Review of International Economics 1:145-63.

3.Aranđelović, Z. (2004). Nacionalna ekonomija, Ekonomski fakultet, Niš

4.Arsić, M., Gligorić, M. M., (2024) Uticaj fundamentalnih faktora na rast privrede Srbije, Naučni skup: Ekonomija: privredni razvoj Srbije i njegove determinante, SANU, Beograd

5.Bajec, J., Joksimović, L. (2004). Savremeni privredni sistemi, Ekonomski fakultet, Beograd

6.Baldwin, R., Braconier, H., & Forslid, R. (2005). Multinationals, endogenous growth and technological spillovers: Theory and evidence. Review of International Economics, 13(5), 945- 963. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-

9396.2005.00546.

7.Bek, U. (2003). Virtuelni poreski obveznici, u: Globalizacija–Mit ili stvarnost, Sociološka hrestomatija (priredio Vuletić Vladimir), Beograd, Zavod za udžbenike i nastavna sredstva

8.Besley, T., (1995) „Property Rights and Investment Incentives: Theory and Evidence from Ghana“, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 10, No 5.

9.Burda, M., Viploš, Č., (2012) Makroekonomija, Evropski udžbenik, Ekonomski fakultet, Beograd

10.Cvetanović, S. (2004). Teorija privrednog razvoja, Ekonomski fakultet, Niš

11.Devetaković S., Jovanović Gavrilović B., Rikalović G. , (2010), Nacionalna ekonomija, Ekonomski fakultet, Beograd

12.Dragutinović, D., Filipović, M., Cvetanović, S., (2012) Taorija privrednog rasta i razvoja, Ekonomski fakultet, Beograd

13.Drašković, V. (2003). Kontrasti globalizacije, Beograd, Kotor; Ekonomika, Fakultet za pomorstvo.

14.Đurić-Kuzmanović, T. (2001). Ekonomika Jugoslavije: ekonomika razvoja i tranzicije, Alef, Novi Sad

15.Fatas, A., Mihov, I., (2013), „Policy Volatility, Institutions, and Economic Growth“, The Review of Economics and Statistics 95(2): 362-376.

16.Feldstein, M., Harioka, C., (1981), „Domestic Saving and International Capital Flows“, the Economic journal 90(358), pp. 314-329.

17.Filipović, M., Nikolić, M.,(2017), Razvojna politika Srbije u 2017.- predlozi za promenu postojeće politike podsticaja, Zbornik radova: Ekonomska politika Srbije u 2017. godini, Naučno društvo ekonomista Srbije i Ekonomski fakultet Beograd, str. 157-177.

18.Gregori, R. P., Stjuart, C. R., (2015) Globalna ekonomija i njeni ekonomski sistemi, Ekonomski fakultet, Beograd

19.Hausmann, R., Hidalgo, C. A., Bustos, S., Coscia, M., & Simoes, A. (2014). The Atlas of Economic Complexity: Mapping Paths to Prosperity, Mit Press.20.https://data.worldbank.org, pristup: decembar 2024.

21.Ilić, B. (2005). Razvojne šanse zemalja u tranziciji u uslovima ,,nove ekonomije”, Institucionalne promene kao determinanta privrednog razvoja Srbije, Ekonomski fakultet, Kragujevac

22.Jovanović Gavrilović, B. (2010). Serbia Economic Growth Quality–Critical Analysis, ECONOMIC GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT OF SERBIA NEW MODEL

23.Kitanović, D., Golubović, N., Petrović, D. (2008). Osnovi ekonomije, Ekonomski fakultet, Niš

24.Leković, V. (2008). Komparativni ekonomski sistemi, Ekonomski fakultet, Kragujevac

25.Levine, R., Renelt, D., (1992), „ A SensitivityAnalysis of Cross-Country Growth Regressions,“ American Economic review, American Economic Association, vol. 82(4) p. 942-963, September.

26.Lim, J. J., (2014), „ International and Structural Determinants of Investment Worldwide“, Journal of Macroeconomics, vol. 41(C), p 160-167.

27.Madžar, Lj. (2002). Teorija proizvodnje i privrednog rasta, I tom, Savezni sekretarijat za razvoj i nauku, Beograd

28.Maksimović, Lj., Kostić, M., (2019), „Dinamika i implikacije odnosa stranih direktnih investicija i tekućeg bilansa odabranih zemalja Balkana“, Zbornik radova Ekonomska politika Srbije u 2019. godini, Naučno društvo ekonomista Srbije, SANU i Ekonomski fakultet Beograd, str. 61-74.

29.Mankiw, N. G., Romer, D., David, W., (1992), A Contribution to the Empirics of Economic Growth, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(2), 407- 437.

30.Marjanović, V. (2015). Strukturne promene i strukturna transformacija u savremenoj razvojnoj ekonomiji. Ekonomske teme, 53(1), 65-84.

31.Mesarić, M. (2002). Uloga države u savremenim tržišnim privredama, Makroekonomsko planiranje i tranzicija, Beograd

32.Mićić, V. (2016). Strukturne promene i konkurentnost prerađivačke industrije Republike Srbije, U: V. Marinković, V. Janjić, i V. Mićić, (Red.). Unapređenje konkurentnosti privrede Republike Srbije (str. 153-161). Kragujevac, Republika Srbija: Ekonomski fakultet Univerziteta u Kragujevcu.

33.Ministarstvo finansija (2011) Izveštaj o razvoju Srbije 2010. Beograd.

34.Petrović, P., Berčerević, B., Minić, S., (2024) Privredni rast Srbije: determinante i budući izgledi, Naučni skup: Ekonomija: privredni razvoj Srbije i njegove determinante, SANU, Beograd

35.Pokrajac, S. (2002). Tehnologija, tranzicija i globalizacija, Beograd

36.Rosić, I. (2002). Rast, strukturne promene i finkcionisanje privrede, Komino trade, Kraljevo

37.Šoškić, D., (2024) Tržište kapitala kao faktor rasta investicija i privrednog razvoja u Srbiji,Naučni skup: Ekonomija: privredni razvoj Srbije i njegove determinante, SANU, Beograd

38.Timmer, C. P., & Akkus, S. (2008). The structural transformation as a pathway out of poverty: Analytics, empirics and politics. Working Paper, No. 150.

39.UNIDO. (2013). Industrial Development Report 2013, Sustaining Employment Growth: The Role of Manufacturing and Structural Change. United Nations Industrial Development Organization

40.Veselinović, P. (2006). Oživljavanje privredne aktivnosti u uslovima globalnih ekonomskih promena, Ekonomske teme, br. 1-2, Niš

41.Vukotić, V. (2001). Makroekonomski računi i modeli, CID, Podgorica

Published in

Vol. 11 No. 1 (2025)

Keywords

🛡️ Licence and usage rights

This work is published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

Authors retain copyright over their work.

Use, distribution, and adaptation of the work, including commercial use, is permitted with clear attribution to the original author and source.

Interested in Similar Research?

Browse All Articles and Journals