THE ROLE AND SIGNIFICANCE OF AUDIT SAMPLING IN THE MODERN ENTERPRISE

Abstract

Auditing is an activity that is present in today's world at every step and in every branch of the economy. When we mean the audit of financial operations, it means that the audit is carried out on the total financial operations of the entity in a certain period of time or includes the audit of a specific economic sector. The audit of financial operations is carried out with the aim of determining the actual financial condition of the entity in a certain period. It is also carried out in situations where there is suspicion of misuse of financial documents or in other situations when management authorities require it. It differs from other types of audit, not only because the subject of the audit is financial statements, but it is necessary that its auditors possess professional and ethical qualities. The audit of financial statements includes the collection and evaluation of evidence in a systematic way, which creates a basis for validating financial statements and checking their compliance with international accounting standards and international financial reporting standards.

Article

Introduction

The audit of financial statements is preceded by the collection and evaluation of evidence, and for the purpose of the auditor's independent and competent expression of opinion. In order for an auditor to express his opinion, it is necessary to have evidence and other financial documents. Each piece of evidence is individually evaluated, judged, interpreted and compared by the auditors with the defined international standards, before expressing the opinion of the auditor whether the financial statements have been prepared in accordance with the regulations and whether the entity's financial operations are regular. In order for the auditor to be able to carry out all these activities, it is necessary to have certain analytical, interpretation and connection skills. It is important that the evidence is objective and not subjective in nature, because in this way the auditor's position when judging the evidence is unbiased. Every audit needs to have its implementation strategy. It should be formulated in the right way, in order to adapt to a certain situation, that is, to modify a possible situation in the financial report.

According to auditing standards SAS No. 39, Audit Sampling (AICPA, 1985), as well as International Accounting Standards - IAS, the sampling audit method is defined as the application of audit procedures to less than 100% of the items included in the balance or in a set of business events, whereby those procedures were applied for the purpose of valuing some significant items of that balance or set.

Which will further mean that sampling in audit means drawing conclusions about the whole based on a representative part from that whole.

It is generally known from the classic literature dealing with audit procedures and sampling methods (see, for example: Vance and Neter (1956), Arkin (1984), Robertson and Davis (1988) and Guy et al. (2001).) or others) to use two sampling approaches: (1) statistical, ie. probabilistic samples, and (2) non-statistical samples, i.e. non-probabilistic samples.

Determining the sample size

Regardless of whether the auditor uses non-statistical or statistical sampling, the same basic factors are determined in the process of determining the sample size (Boynton & Johnson, 2006). The following Table 1 presents the basic factors that affect the sample size. However, when the auditor makes his professional judgment regarding the presented factors, the following formula is used:

KV ´ FO

n = DG - (PG ´ FE )

where KV = book value of the population being tested, FO = reliability factor for the assigned risk of wrong acceptance, DG = permissible - acceptable error, PG = expected error, FE = expansion factor for the expected error.

Let's explain these parameters in more detail

The accounting value of the population that is the subject of testing is based on the fundamental premise when determining the accounting value in the procedure of determining the volume of the sample (Ili ć et al., 2022), which is the precise definition of the population (MSR, 2006).

ble 1: Factors affecting sample size

|

Larger samples |

Factor (ratio to sample size) |

Smaller samples |

|

A larger population with a higher book value requires a larger sample. |

Book value of the population (direct relationship) |

A smaller population with a lower book value must be effected on a smaller sample. |

|

A smaller sampling risk results in a larger sample. |

Risk of false acceptance (inverse relationship) |

Higher sampling risk results in a smaller sample. |

|

A smaller amount of permissible error (determined by the auditor) determines a larger sample. |

Tolerable error (inverse relationship) |

A larger amount of permissible error (determined by the auditor) results in a smaller sample. |

|

The closer the values are between the allowable and expected error, the larger the sample. |

Expected error (direct relation) |

The larger the difference in value between the allowable and expected error, the smaller the sample. |

Source: Ciarko & Paluch-Dybek (2022), Craig (2017) and Giuliani (2016)

The amount of the book value has a direct impact on the volume of the sample - the higher the book value, the larger the volume of the sample (Majstorović, 2021).

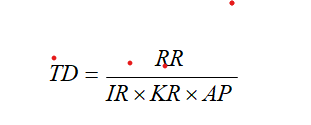

The reliability factor for the assigned risk of incorrect acceptance is determined by applying the audit risk model (Bučalina & Pejovi ć, 2022), as follows:

where: TD – level of detailed testing, RR – audit risk, IR – inherent risk, KR – control risk, AP – audit procedures.

The audit risk model, experience, and professional judgment are essential for determining the level of acceptable risk (Kostić, 2020). Namely, the risk of wrong acceptance has an inverse effect on the sample size (volume) – the lower the level of the specified risk, the higher the level of the sample volume.

The reliability factor is empirical in the following Table 2 and is based on the risk of wrong acceptance determined by the auditor and the zero number of errors, in relation to the predicted number of errors (Vukša et al., 2020). For example, the auditor determined a 5% risk for wrong acceptance. The reference factor of reliability (reliability) is 3.0 based on Table 2.

Table 2. Calculation of the reliability factor

|

|

Reliability factors (reliability) for zero deviation |

|||||||

|

Risk of wrong acceptance |

||||||||

|

1% |

5% |

10% |

15% |

20% |

25% |

30% |

37% |

|

|

Reliability factors |

4.61 |

3.00 |

2.31 |

1.90 |

1.61 |

1.39 |

1.21 |

1.00 |

Of course, if the excesses are non-zero, e.g. 1,2,3,...n, then the table given in the AICPA Audit and Accounting Guide: Audit Sampling applies (as for the null option).

Allowable (tolerable) error (DG) is the maximum possible error in the account before it is determined as a material error (Avakumović et al., 2021). In the process of specifying this factor, the auditor should look at errors on individual accounts in the context of aggregation (accumulation) with errors on other accounts, all of which (cumulatively) can cause the financial statements as a whole to be materially wrong. DG has an inverse effect on the sample size – the smaller the DG, the larger the sample size (Avakumović et al., 2021a).

Expected errors (OG) and expansion factor (FE) in the sampling procedure, the auditor does not quantify the risk of wrong rejections (Ivanova & Ristić, 2020). Namely, this risk is controlled indirectly by determining the expected error (OG), which is inversely related to the risk of false rejections and directly related to the sample volume (Gold et al., 2015). Expected error (EO) is the amount of error that the auditor expects in the population (Halkos & Nomikos, 2021). The auditor uses prior experience and knowledge of the client and professional judgment to determine the size of the OG (Luque-Vílchez & Larrinaga, 2016). The auditor must bear in mind that an excessively large estimate will unnecessarily enlarge the sample, while an estimate that is too low will result in a high risk of erroneous rejection.

The expansion factor (FE) is only necessary when errors are expected (Landman, 2020). It is obtained from Table 3, using the risk of false rejection, determined by the auditor. The lower the specific risk of false rejection, the higher the FE (Stevanović et al., 2019). Like expected error, FE has a direct impact on sample size (Larrinaga & Bebbington, 2021). The combined effect of expected error and FE is then subtracted from the tolerable error in determining the sample size.

Table 3. Expansion factors

|

|

Expansion factors for expected errors |

|||||||

|

Risk of wrong acceptance |

||||||||

|

1% |

5% |

10% |

15% |

20% |

25% |

30% |

'37% |

|

|

Expansion factors |

1.90 |

1.60 |

1.50 |

1.40 |

1.30 |

1.25 |

1.20 |

1.15 |

Calculating the sample size

The illustration works in the case where KV= €600,000; FO = 3.0; DG = €30,000; OG = €6,000; EF=1.6. Then the sample size is calculated as follows (Monciardini, Bernaz & Andhov, 2019):

€600.000 ´ 3,0

![]() n = €30.000 ´ (€6.000 ´1,6)

n = €30.000 ´ (€6.000 ´1,6)

The obtained result indicates to us the fact that the elements for determining the sample are based on the auditor's experience, ie. his expert judgment potential. In other words, it is a matter of auditor's judgment how much error is expected in the population, for example. €6,000, as well as the expected number of deviations, 0,1,2,...,n. In our case zero deviation is expected.

Evaluation of sample results

In the process of evaluating the sample results, the auditor calculates the upper limit of error (GGG) on a sample basis and compares them with the tolerable error (DG) specified in the sample design procedure (Nadoveza, 2022). If the GGG is less than or equal to the permissible error, the sample result supports the conclusion that the book value of the population is not wrong, more precisely, it is not greater than the permissible error (DG) which is determined based on the risk of wrong acceptance (Todorović, 2021).

The upper limit of error (GGG) is calculated based on the formula (Galjak, 2022), which follows

GGG = PG + DRU

where in

PG = total amount of total projected error per population DRU = tolerable sampling risk.

The results obtained on a sample basis are used to determine the total projected error (PG) at the population level. If the error is not found in the sample, the PG factor in the above formula is one zero, ie. zero €, Din, $, etc. (Milanović, 2022).

In the case where there is no error, the Sampling Risk Factor (DRU) contains only one component referred to as the Basic Precision (BP), which represents the amount of estimated error at the population level, even in the case where no error is found at the sample level. The amount of error at the population level is obtained by multiplying the confidence factor (FO) for zero deviation by the determined risk from the Table for determining the risk of false acceptance by the sampling interval (SI).

Given that the value of PG is zero (no errors were found in the sample), DRU=€20,454, which is less than €30,000 - permissible errors, determined by the auditor. Thus, when errors are not found but are expected, the auditor can conclude that the book value of the population does not exceed DG - acceptable error.

If the errors are identified in the sample, the auditor must consider (calculate) the total value (total) of projected errors of the population, and the permissible level of audit risk and determine the upper level of deviation error, which is the basis for comparing GGG with DG.

Conclusion

An independent and objective examination and expression of opinion on the validity and compliance of financial statements with international standards constitutes an external audit. To conduct an external audit, it is necessary to collect and evaluate evidence on the basis of which the auditors form their opinion. Certain evidence is collected and evaluated using a sampling method. The sampling method is based on a statistical and non-statistical approach. Unlike the statistical approach, which is based on objective reasoning, where the results are judged mathematically in accordance with the theory of probability, the non- statistical approach is based on subjective reasoning. The auditors, during the audit of the entity's financial operations, consider whether there is an internal financial control system within the entity and whether it functions smoothly. A set of internal political activities and procedures, adopted by the management of the entity, and in order to achieve the defined goals and tasks, are the measures taken in the system of internal financial control. The internal financial control system includes the accounting system, control policy and control environment. The management of the entity is responsible for establishing the system of internal financial control in the entity and for its functioning, while the auditor is responsible for its evaluation and judgment, as well as for the assessment of control risk. The functioning of the internal financial control system at a specific entity enables auditors to work smoothly when auditing financial statements, by reducing the scope and time of their collection and evaluation of evidence.

References

2. Avakumović, J., Avakumović, J., Milošević, D., & Popović, J. (2021a). Zadovoljstvo zaposlenog nastavnog osoblja kroz prizmu AMO modela – primer: Republika Srbija. Akcionarstvo, 27(1), 107-120.

3. Avakumović, J., Marjanovića, N., Rajković A. (2021). Menadžment cene kapitala u svrhu donošenja investicionih odluka preduzeća. Akcionarstvo, 27(1), 89-106.

4. Bučalina, M. A., & Pejović, B. (2022). Teorijska konceptuelizacija preduzetništva. Društveni horizonti, 2(4), 235-253.

https://doi.org/10.5937/drushor2204235B

5. Ciarko, M., & Paluch-Dybek, A. (2022). Efektivnost unutrašnje kontrole u jedinicama lokalne samouprave. Društveni horizonti, 2(3), 75-84.

https://doi.org/10.5937/drushor2203075C

6. Craig, G. (2017). The UK’s modern slavery legislation: An early assessment of progress. Social Inclusion, 5(2), 16–27. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v5i2.83

7. Galjak, I. (2022). Pravno uređenje investiranja u javnom sektoru. Revija prava – javnog sektora, 2(1), 27-44.

8. Giuliani, E. (2016). Human rights and corporate social responsibility in developing countries’ industrial clusters. Journal of Business Ethics, 133(1), 39–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2375-5

9. Gold, S., Trautrims, A., & Trodd, Z. (2015). Modern slavery challenges to supply chain management. Supply Chain Management, 20(5), 485–494. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-02-2015-0046

10. Halkos, G. E., & Nomikos, S. N. (2021). Reviewing the status of corporate social responsibility (CSR) legal framework. Management of Environmental Quality: An

International Journal, 32(4), 700–716. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEQ-04-2021-

0073

11. Ilić, B., Milojević, I., & Miljković, M. (2022). Uloga akcionarskog društva u održivosti razvoja kapitala. Održivi razvoj, 4(1), 19-28.

https://doi.org/10.5937/OdrRaz2201019I

12. Ivanova, B., Ristić, S. (2020). Akumulacija i koncentracija kapitala.

Akcionarstvo, 26(1), 26-34.

13. Kostić, R. (2020). Revizija ostvarivanja ciljeva budžetskih programa. Održivi razvoj, 2(1), 41-52. https://doi.org/10.5937/OdrRaz2001041K

14. Landman, T. (2020). Measuring modern slavery: Law, human rights, and new forms of data. Human Rights Quarterly, 42(2), 303–331. https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.2020.0019

15. Larrinaga, C., & Bebbington, J. (2021). The pre-history of sustainability reporting: A constructivist reading. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 34(9),

162–181. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-03-2017-2872

16. Luque-Vílchez, M., & Larrinaga, C. (2016). Reporting models do not translate well: Failing to regulate CSR reporting in Spain. Social and Environmental Accountability

Journal, 36(1), 56–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969160X.2016.1149301

17. Majstorović, A. (2021). Pravni okvir savremenog budžetskog računovodstva.

Finansijski savetnik, 26(1), 7-24.

18. Međunarodni standardi revizije (MSR). (2006). "Populacija predstavlja sve podatke iz kojih se izvlači uzorak i o kojima revizor želi da donese zaključak", str. 234.

19. Milanović, N. (2022). Veza internih kontrola i revizije u javnom sektoru.

Finansijski savetnik, 27(1), 65-76.

20. Monciardini, D., Bernaz, N., & Andhov, A. (2019). The organizational dynamics of compliance with the UK modern slavery act in the food and tobacco sector. Business & Society., Article 765031989819. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650319898195

21. Nadoveza, B. (2022). Uloga ljudskih resursa u sportskim organizacijama.

Menadžment u sportu, 13(1), 13-24.

22. Stevanović, T., Antić, Lj. & Savić, A. (2019). Specifity of performance measurement in the ministry of defense and the Serbian armed forces, Facta universitatis, Series:Economics and Organization,Vol.16, No 3, pp. 283-297.

23. Todorović, Lj. (2021). Kontrola u javnom sektoru. Revija prava – javnog sektora, 1(1), 7-22.

24. Vukša, S., Anđelić, D., & Milojević, I. (2020). Analiza kao osnova održivosti poslovanja. Održivi razvoj, 2(1), 53-72.

https://doi.org/10.5937/OdrRaz2001053V

25. W.C. Boynton, R.N. Johnson, “Modern Auditing”, JohnWilley & Sons, Inc. 2006. str. 570-580.

Published in

Vol. 9 No. 1 (2023)

Keywords

🛡️ Licence and usage rights

This work is published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

Authors retain copyright over their work.

Use, distribution, and adaptation of the work, including commercial use, is permitted with clear attribution to the original author and source.

Interested in Similar Research?

Browse All Articles and Journals